Notes from the Author

I have always felt ill-at-ease about obituaries of famous people, especially famous people I knew personally. The writer of the obit invariably holds back those less panegyric elements of the famous dead person, perhaps, or likely, out of respect for the dead, and this is especially true when the famous dead person was, by and large, respected. Such obits tell only part of the truth.

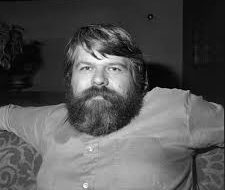

The obits which rose to the surface in the wake of Chuck Kinder’s passing have been such obits, glowing hallmarkograms of “the beloved teacher of writing at the University of Pittsburgh.” This much is true: Kinder’s finest achievement by any measure is his novel Honeymooners: A Cautionary Tale, but Kinder’s greatest claim to fame involves his former student Michael Chabon who in his own novel Wonder Boys portrays Chuck Kinder as the Pittsburgh outlaw writing professor Grady Tripp. Tripp-Kinder is the book’s narrator. In the film of the book, Professor Tripp is played by Michael Douglas. I can see Chuck’s self-deprecating, smirky dismay had he known his student’s name and book would appear atop every one of his own obits.

Kinder died in early May of this year. Why am I rushing to get my say in? I consider this a proper time to tell of my time with Chuck Kinder. The following is not a response to his death. I wrote this item two years ago. That said, every death is different, as is every reaction to death. In the case of this death, I don’t subscribe to the common law that I should respect the dead with my silence at a time like this. First, it smells too much like Church Rules; second, there will be no time when Kinder is not dead just as the same will be true of me; and third, Chuck disrespected me, utterly and eternally, so I’ve concluded I’d better speak up now or forever hold my truth.

If you have a problem with that, please don’t read on. If you prefer instead to live with your eyes wide open, open wide and see what else happened during those gold-patina literary days in “The Paris of Appalachia,” a term Kinder is believed to have coined, and I believe it, as it expresses the breadth of Chuck’s ambition and the depth of his roots in his hillbilly past. – DJB

A Cautionary Backtale

Dennis James Bartel

I hear he is not well. I hear he had a stroke, or worse. I don’t know his condition. We haven’t spoken since the early eighties. Neither am I well. As Papa must have said somewhere, the bull is rushing toward us all. All the more reason to tell this story while Chuck still lives, so he can respond, or his many Kindernicks can respond for him. He is a great man in Pittsburgh, I hear, a hero. I’ve kept quiet, out of respect for him and fear of him, but also, I needed to make a more thorough assessment of Wonder Boy’s actions. After all, Kinder has always been a man of action, an outlaw writer. For three decades, I’ve made my assessment, quietly, in private. I still don’t know if I’ve got it right. You tell me.

Before I left my morning radio classical DJ job in L.A. to come to Pittsburgh, I told the English professor who reviewed books for us on-air, that I was leaving the station to go east and write novels. Jascha Kessler was his name. We had him on every other Wednesday at 9:00 in a three-minute slot he invariably filled with nine minutes of impassioned professorial analysis which quickly left the book at hand behind and reached out into the issues of the day. Kessler seemed surprised by the news of my leaving, but quickly recovered and put his senior hand squarely on my shoulder. He seized my eye contact and cautioned me, “If you want to write a novel, Dennis, you’re going to have to sit on your ass.” The mild profanity coming from proper-speaking Dr. Kessler made me blink. His words remained alive, buried in my memory until they took root.

I arrived in Steel City in time for the fall semester, 1980, leaving behind a new girlfriend with whom I was still in the sweaty throes of ecstatic new sex. Poor life timing. The city was sweltering. Pissburgh, I thought. I took up residence in a third-floor apartment, a former maid’s quarters in a formally great mansion from the Big Steel Era, near the reservoir, Highland Park. A stylish fortyish couple (she a doctor, he a Haitian art dealer) owned the house and rented out the top floor to me. I like to think I was a safe bet, single grad student, low key, a writer, no criminal record, no crimes at all in fact, on record.

Another prof, Bruce Dobler, met with me and another incoming fellowshipee who told of his vast reading and his many years in the coat retail business. We met at a bar. It was an orientation class, a three-day, how-to-teach seminar he conducted for a maximum of two students, because that’s how many could fit in a booth with him. We drank beers and ate. Dobler was what he ate, as we all are, and Dobler ate hamburgers and bacon. Not much was said about teaching during this teaching primer. At one point, Dobler offered his daughter to both of us (me and the coat retailer), his senior high school daughter! “Maybe you could have sex with her.” I was sure he was joking. Then I wasn’t sure. “She needs to learn some things,” said Dobler, “before she gets to college. Take her out to a movie and dinner and fuck her in the ass. I don’t care.”

Dobler told us Kinder was coming to Pitt with a reputation for making trouble. “Trouble as in bad boy, big-grinin’, hard-drinkin’, rifle-totin’ trouble.”

“—Tokin’?” I joked.

Dobler laughed, sort of. “He’s supposed to be the real deal, a literary outlaw. He’s supposed to be a friend of Raymond Carver.”

I had no idea who that was, not yet. The former coat salesman knew Carver’s books and was quick to say so, as he was quick to tell you about all the books you haven’t read. Evidentially, Carver had two books, both harrowing in their debasing depictions of personal self-destruction through the annihilation, or, just short of annihilation, the minimalism (aka incarceration) of self-worth. Imprison the reader inside walls which allow the use of only a few hundred words, not many of them beautiful or artful or deeply expressive or anything but the minimum, and watch your self-worth plummet. That and alcohol.

One of my first impressions of Kinder (and this seemed to be the same for many people, reporters in particular) was that sometime as a young scribbler Chuck must have swallowed the Hemingway ethos of The Writer’s Life, hook, line and old man. Live large, don’t apologize. Be true to your art, if not always to yourself, or your lovers or your friends, or anyone else. He believed in the gold standard values of clarity, earned understatement and the code of the hunter.

Whatever his wild man notoriety, within the painted walls of the University of Pittsburgh’s tremendous, skyward-reaching Cathedral of Learning, the situation brought out the tweedy good professor in him. Kinder was too busy making friends to make trouble. Chuck was certainly good to me. Right away we were simpatico. Dad taught me to look in someone’s eyes and trust what I saw. Sometimes you’re wrong, but not as often as you’re right. Kinder looked real to me, but maybe I was only responding to the strong-armed West Virginy charm I’d seen him put on others. I thought, We’ll see. I had not come to Pissburgh to be seduced.

Kinder was teaching one of the two writing seminars that semester. I signed up. Raymond Carver’s books of drunken nihilism were on the syllabus. I devoured them quickly, then went back for seconds. Kinder struck me as a clear thinker and straight talker. He played up his rural roots, his persona as the dumb plain honest, shit-kickin’ hillbilly, but I learned from Dobler that during the hiring process Kinder had called himself “a Matthew Arnold man.” This hillbilly studied at Stanford under Stegner’s auspices and knew which end of a book was up. In this way, we were similar. I came from the Blue Collar Belt. Dad drove a semi, Mom operated a PBX. I, also, had read a few books, and earned the terminal degree in writing at an elite writing program. Chuck was about a decade older and the more I discovered about his path to The Cathedral of Learning the more I convinced myself I was on a similar path by using a teaching fellowship at Pitt to buy myself a couple of years to write. Perhaps Chuck saw me seeing that in him.

I checked out the only copy of Kinder’s work I could find listed in the Pitt library, Snakehunter, published by Knopf six years earlier. I must confess, it felt like an underwritten novel and didn’t leave much of an impression on me. The most striking moment was a denouement in which Ernest Hemingway, appearing as a character, sodomizes the narrator-author. It was grotesque. I had to look away.

In workshop, Kinder spoke appreciatively of my manuscripts, nothing hyperbolic, and not without finding weaknesses. Chuck’s manner when giving criticism was non-threatening, positive, easy to absorb, offered from someone who had been hurt in workshops like this and who had hurt others. Sometimes his critical knife was sharp and it stung as he performed his fine surgery, but his cut was sure and right. I never saw him intentionally humiliate a student. He patronized only occasionally and then it was a last-chance-for-an-idiot kind of patronizing. Chuck seemed to understand something important about each of us – we were trying with all our life’s strength to do the impossible.

I wrote like a man released from prison on a limited furlough, and quickly the pages piled up and a novel began to take shape. But you have to leave the typewriter for a few hours each day and so I began to acquire a repertoire of lonely drinking holes, including a no-name neighborhood bar at 5th and Bigelow, around the corner from the Cathedral. It was darker than most bars during the day. Student lifeforms were never completely absent but neither did they ever overwhelm the bar. A lot of regulars walked home.

One weekday afternoon at this no-name bar I looked up from my green Rolling Rock and caught a glimpse in the mirror of Kinder across the smoky room, sitting by himself in a deep and wide black vinyl booth. He caught my eye and gestured me over.

It would be the first of many times we sat together and drank and talked of the good things – writing, women, the true work, muddy boots (I caught a whiff of disappointment coming off Kinder when I couldn’t keep my end up on hunting; he never brought it up to me again). I was impressed at his off-handedness about this serious matter of literary art. I began to compile names of authors to read, most of them of the hard-knuckled, raw pain variety – Jim Harrison, Barry Hannah, Larry McMurtry, Thomas McGuane. “Read‘m now before you really get down to writing.”

Oh, and what have I been doing up to this point? I thought it but did not say it. I proceeded to read every one of these authors and many of their roughshod associates. Sucked them down approvingly. I even spent an afternoon with Hannah, who had come to Pittsburgh to attend Pitt’s writers’ conference, a stage event. I met Hannah at the Cathedral. No sooner had we shook hands when David Halberstam approached Hannah to say good-bye. They clasped hands. “Take care, Barry,” said the lanky great reporter with the fondness of a dear friend.

It was one of those rare-but-perfect days in Pittsburgh. Hannah and I walked to the radio station, about a quarter-mile. (Yes, I was back to spinning disks for you on the radio, chiefly so I could eat and pay for my former-maid’s literary den. Have you any idea what a teaching fellowship pays?) I considered having to do occasional work for WQED a pit stop, a slip-slide outside the straight and narrow, and a violation of my commitment to writing, but I had to do it.

It was a long interview before the mike. I was flush with The Tennis Handsome. Barry said he didn’t understand writers who work on novels for six or seven years, people like James Joyce. “I don’t have that kind of attention span.” He laughed and told me he’d written The Tennis Handsome, with its magnificent wide leaps between sentences, in six months, alone in his room with “Hendrix and marijuana.” Remember, this was back in the dayz when the very words “Hendrix” and “marijuana” were still illicit in Pittsburgh.

Just as I agreed with Chuck that Barry Hannah and the others were important writers to read, I agreed with Chuck on everything, including the literary practice of yanking people from your past for use as characters in your fiction. “I can’t make up anything,” Chuck said, “so sometimes I drudge up stuff from the past and stick it in.”

As a junior colleague, as a student, as a friend who was trusting him more and more, I lamented my pain to Chuck, my long-distance romance, how it hurt, how distracting, how hard. Her name was Judith but with me she went by Joder. She had moved back in with her mother who lived alone in the family’s longtime home, a 15-room Pasadena Palace walking distance from The Huntington Library, with a royal curving staircase and a grand room where stood two pianos, a mini-grand made by Knabe and a Steinway Grand, with plenty of room left for chamber musicians and guests. By moving back onto the “odious stage of my youth,” Joder could save money and stay out of the way of sexual predators until I returned for her. “What can I say, she loves to fuck.” Chuck listened intently and patiently. He said he sympathized. He knew how it felt. His wife Diane was still in San Francisco, in her job.

I told Chuck I’d read Snakehunter and praised it in as few words as possible. He looked pleased. He offered to loan me a copy of his second novel. I didn’t know he had a second novel. Yeah, said Kinder, it was the book that got him the job at Pitt, and then with the next breath, in his distinctly WV brand of phony self-deprecation, he scoff-chuckled and told me the book was already out of print. It had been published by Harcourt Brace, not Knopf, just twenty months ago. He had only one copy, he vowed to me, so please be sure to give it back.

The Silver Ghost struck me as a more proper roman à clef, and a more finely made novel, for a while. Jimbo Stark (Kinder’s name for himself, which he plucked from James Dean’s character in Rebel Without A Cause) is about Kinder’s age, having grown up in West Virginia. He imagines (or hallucinates) he is James Dean. Eventually, Hemingway shows up (again?) under the name Jake Barnes (really) and causes havoc, sans buggery.

So what happened? In the basement of my Highland Park garret, while reading The Silver Ghost, I was doing my one load a week of laundry and I set the book on the washer as I loaded the clothes and the tub filled with water and I carelessly knocked the book into the tub.

Mortified is the word. During the next few days, I rushed to find a copy to replace it, but none of the bookstores in Pittsburgh had it. Even Jay’s Book Stall, your most reliable and resourceful source, couldn’t order it, out of print. I called Harcourt Brace to plead my case. They sent me a copy for a price. I finished reading the book and gave Chuck the new copy, explaining how I had spilled vodka on his book, sorry.

Chuck seemed to like that. Over weeks, within these dark vinyl confessionals in a no-name bar, Chuck Kinder made many shock-stopping astute observations about the novel I was furiously writing. He said he liked it, he supported it, but I had plenty to work on and plenty I had already worked on I would need to work on more. I took his advice. I did what he said. What greater love hath any writer?

Kinder told me he was writing a new book, and it meant so much to him he kept the manuscript in the bottom of the refrigerator, so in case a fire burned down his house at least he would still have his novel-in-progress. He said the story was about his time in the Bay Area, and his friendship with Raymond Carver. He asked if I’d like to read part of it.

*

Coming from Southern California, I had yet to get appropriately suited up for the western Pennsylvanian winter. I often went without a hat. For me, hats were for baseball diamonds. I refused to buy one of the Michelin Man puff coats I saw everywhere. For the first weeks of classes, as the temperature fell faster than the leaves, I showed up to teach in a green-gray blazer, a tie and khakis. It was the first time in my life I’d worn a tie on a regular basis. The tie often got windblown over my shoulder without my noticing, and I’d walk into class looking affected. Students would inform me of my mis-positioned tie as I began to lecture. It must have distracted them.

The classes I taught resulted in students dropping blizzards of paperwork before me in see-through plastic binders, plain tan folders, stapled, paper-clipped, out of order, typed &/or hand-written, chest-pounding & chest-heaving. From the Thesaurus-cobbled third-person narrative to the late-night amphetamine improvisation, the stories of these quite ordinary students piled higher on my make-shift desk at home. I earnestly corrected their semi-literate mistakes, and praised those who wrote better than the rest, which didn’t mean much because the rest were dreary passersthru. It was all relative, all on the curve.

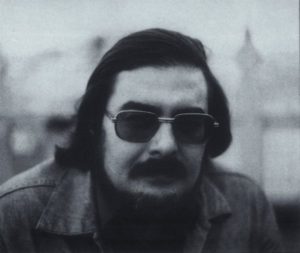

Except for one student, Michael. When I read his first assignment, the thought crossed my mind he had plagiarized some author of the 1920’s. The writing was slightly mannered, faintly Fitzgeraldian. It was also much too good. The second work Michael delivered contained playful echoes of the previous class discussion on story structure, chiding his classmates, gently sassing his teacher. The writing was fresh, ornamented, and hip. I didn’t know what to say. In the third assignment, there was another handful of astonishing pages. It was as if Michael was toying with the assignment, something about point-of-view, like a teenager playing with his baby sister’s stuffed lion, and then losing interest and tossing it aside.

I asked Michael to please stop by my cubicle. He took his time, but then one afternoon he popped in. We chatted. I told him I was giving him a pass on the rest of the assigned work. I said I thought he was some kind of special, and if he only matched the page-count requirement for the class he was free to ignore the assignments and write whatever he wished. He liked the idea of writing a novel. I promised he would receive an “A” regardless of what he wrote. “Just fill up pages.” Michael accepted his new-found freedom and left the cubicle with what looked like a look of What-is-this-really?

He took his freedom and produced nothing. Weeks passed. While the paper deluge from other students ebbed and flowed, depending on how much time I had to give to my novel that week, Michael’s hands remained empty at the end of class. Another open box in my grade book next to the name Chabon. Had I made a young teacher’s mistake? Then in the final few weeks of the term, Michael came forth with a surge of words, page after page after page … some of it a little goofy and show-off, as Michael seemed to be by nature, some of it seemingly fragments of a novel, but then other pages were far afield, most of it both exhilarating and deflating to read. This young guy with unkempt hair was ten years younger than I, and ten years ahead of me. In my cubicle at the end of the term, I gave him an A-minus, and when he asked why minus I said I felt he had sloughed off in mid-term. “I’ll tell you what I learned, am still learning. If you want to write a novel you’ve got to sit on your ass.”

“Good enough,” said Michael.

“It still counts as an ‘A,’ officially.”

One late-winter, ice-crispy day while I was showing off my steaming hot Joder, in from L.A. for the weekend, we visited Jay’s Book Stall where Michael now worked. He gave us (well, he gave her, and I followed) the grand tour of the tiny book-crammed shop, including a peek at Jay’s impressive stock of gay porn, which was never put on display but was always available. Joder flirted with Michael as she might flirt with the best friend of a younger brother, turning his name into a gesture of affection, “Mik-el.” While I wasn’t looking, Michael slipped a novel to Joder with instructions to give it to me later. She said he said I might like it, it reminded him of me. It was Macho Camacho’s Beat.

The point is, I suppose, in Pittsburgh I experienced the master-apprentice relationship from both sides simultaneously. For Chabon I was, briefly, the master. For Kinder I was the apprentice. I suggested to my apprentice that, seeing as he appeared capable of producing an endless spring of sentences upon splendid sentences, he may like to look into the string quartets of Beethoven, with an ear for how they are assembled architecturally, like a lifelong story. I don’t think he bothered. His favorite band was Rush.

The day came, as we sat in our semi-dark no-name bar, Kinder handed me the first 150 pages of his new manuscript and asked me if I’d tell him what I thought. He said he trusted me with them. This was his only copy. I could have it for only one night. Keep it clear of the vodka. I accepted the sacrosanct papers, took them home, got high’d up, and began to read. Goodgod, the man had leapt forward a delirious distance. This was writing! The sentences flung themselves off the page. It was all I could do to grab them and hold each to my breast. The next morning, I returned the manuscript with my high praise. Kinder said, “Now you are the only person who has read everything I’ve published.” I thought he was talking as if this new manuscript had already been bought by Harcourt Brace.

It would be another two decades and thousands of pages before Kinder’s finest work, the book on which he has hung his legacy, Honeymooners: A Cautionary Tale, was published by his third publisher in three books, Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

As you likely know, Honeymooners is the story of the friendship between Chuck Kinder (who encores as Jimbo Stark) and Raymond Carver. When these two got together they’d slop up a cow’s belly full of whiskey and beer. Their long friendship had its obscene pratfalls and vicious connivances. Booze will do that. But they were still friends and still on the Lit Roller Coaster together. Yippy-eye!

I asked my master if he would head my thesis committee, a momentous moment in my view. I got the impression from recognized literary-aware people that with Kinder backing my novel it had a far far better chance of scoring. Kinder said he’d be glad to serve, waving his arm so as to say, You’ll fly through it with ease.

Sure, Chuck, it’s all so easy, a walk in the park, a sitting duck, a regular honeypot. But wait. Tchaikovsky once cautioned, based on his experience, “There is always one drop of gall in the honeypot.” My drop of gall was another Pitt prof, Eve Shelnutt, a woman so galling she soured my honeypot to the edge of uneatable. She’d been catapulted into The City of Champions by her first book of short fiction, The Love Child, which won some big small press award in Kalamazoo. Shelnutt had previously been at Western Michigan, home of the Broncos, alma mater to Home Improvement’s Tim Allen, and Yankee tattletale Jim Bouton, as well as a drove of donkeys Shelnutt had brought along with her to Pitt, five or six early-to-mid-twenty-something men with sunless white skin and a shared factory ancestry. Her coterie.

At first, I thought, I’ll get along with these Western Michigan grads. I saw the rude wisdom of physical labor in their eyes. Or was that dullness? But before I could make friends with any of them, Shelnutt sized me up quickly and pronounced me the enemy, worse, “the devil,” the kind of writer who would do damage to literature, as many of my kind had already done. Shelnutt’s donkeys, ah-heck, her broncos, ate up her hate. She was fighting a crusade to save the art form from a destiny in literary hell.

Individually, I got on swell with any of Shelnutt’s broncs, one-on-one. I recall a breakfast I spent with one of the most vile, Dan, who came to workshop like a drunk entering a bar intent on fighting, like it was sport. The pancake house that rainy morning was so packed (what else was open Sunday in Pissburgh?) we wound up seated together across a two-person table. There was nowhere else to sit. The back of my chair was flush against the storefront window.

I got the conversation started quickly. “Whadda think of the Tigers this year?”

Dan leaned forward on his elbows. “I think Parrish is going to hit forty home runs, drive in a-hundred, and carry Detroit to second place in the East.”

“Ahead of Baltimore? Whodoyoulike?”

“Ahead of Baltimore and ahead of everyone else, except the Brewers.”

“Best infield in baseball.”

Dan and I had a good conversation over coffee and a pair of $2 tall stacks. Then in the next workshop, the very next day, he was among the rag of mustang ponies who rushed up on tiny legs and cruelly stomped on my work, all the while making savage sounds which echoed Shelnutt’s elitist dictum about the artist’s role and other bullshit.

Come springtime, up three flights to my former maid’s quarters, one-bedroom Highland Park apartment, I and Joder who flew in for a few days of ravenous sex held a small soiree to celebrate the publication of a first book, a novel, by my former teacher Patt McDermid in California. I was publishing Mountainhouse as a final act of my journal/press The Gramercy Review. The quarterly had a solid five-year run, and we’d published a few segments of Mountainhouse by the Stanford grad and Ph.D., but when I left my radio job in L.A., funding, energy, effort and time (all of it mine) ran out on the mag, so this, as Jim Morrison observed, was the end. About twelve people came to the party, which turned out to be more than the garret could bear, seeing as one third of the place, the bedroom which lay in waste, was closed and off limits.

Patt was not there to bask in his literary birthing. Patt taught impoverished kids to read at Lassen College in his hometown of Susanville, where he lived with his wife and their two young children, 4,000 feet up into the northern California mountains. No, Patt wasn’t in my Pittsburgh third-floor apartment that night to see his book launched, he couldn’t make it.

Kinder was there. His black-jacketed bulk dwarfed the other guests. Joder flirted with Kinder, rubbed against him. That’s just kinda what she did. He didn’t seem to mind, nor did he seem to be rubbing back. When I came by, Kinder told me, in a voice lined with faux menace, he’d “found out the real story behind Silver Ghost.” For a second, I had to remember, Silver Ghost? Joder saved me. “You said you spilled vodka on it, on the book, on his copy. I accidentally told him the truth.”

Kinder laughed. He was kidding, I realized before reacting, and oddly enough, he was kidding in a way that I felt we were both in on the joke, just kidding, ok guy.

The A-frame upper-room former maid’s loft was stifling. The owners downstairs ran the central heat all night as if to reproduce the warm tarp of humidity at Port-au-Prince. We, the dozen or so of us, were all pretty moist as we moved through the night, with beer and vodka and Talking Heads. To my knowledge, Kinder left the party without a copy of Mountainhouse. It’s not like I was charging. He could have just taken it and forgotten about it.

Such went my first year in Pittsburgh. That summer I went home to Los Angeles with the intent to convince Joder to marry me and come live in P-town. I admit that seems like a grim offer. Judith picked me up at LAX. On the way to her mother’s Pasadena mansion where I’d be staying the first couple of days before even going home to see my folks, before we had even touched intimately, we stopped by KUSC, where I used to work and where she still worked, only to discover Joder was again having ecstatic sex, with a record distributor. After a summer of frustration and heartbreak I returned alone to “The Paris of Appalachia,” a title believed to have been given to Pissburgh by no less than Chuck Kinder (or at least he didn’t say he didn’t).

No sooner had the bus traveled through the long uterine Fort Pitt Tunnel and I saw again with tired eyes the Ozsome Golden Triangle. Has anyone observed that the Ft. Pitt Tunnel is facing the inescapably phallic Pitt Cathedral? I dropped my duffel bag on the floor of my maid’s quarters apartment, when the phone rang and it was Kinder. This was a surprise, and it could be either very good or very bad. It was neither. Kinder asked me to join him and two other faculty members for a two-day, pre-term pow wow to talk about the writing workshops. When I learned Eve Shelnutt was one of the other two, I hesitated, but quickly found the nerve and agreed, I mean, it was Chuck Kinder asking.

I think it was over Shelnutt that Chuck and I genuinely bonded. So far, I understood I was just another worshiper at Kinder’s feet, not so much worshiping Kinder, but worshiping what Kinder represented, the freedom to write, to live a writer’s life. Now in this confab, we linked arms.

The breach that quickly opened on the first day may be summarized as follows: Shelnutt insisted that writing was rooted in the oral tradition of storytelling, therefore copies of stories must not be distributed in workshops, rather, the author must read the story in class while students “honed their listening skills.”

It’s possible that I might have objected to anything Shelnutt had said, a woman with brake fluid for blood and all the compassion of a slab of limestone. Among her uncountable acts of snobbery and cruelty was one which sent a former A-minus student of mine fleeing The Cathedral of Learning in tears. It was cold, almost dark, and a Monongalian fog was engulfing the campus. Christine ran into me, I saw she was upset, took her aside, asked how I could help her. She explained that in class just then Shelnutt had dismissed her in front of everyone, her, a sharp-eyed college senior brimming with literary aspirations, with the terrible commendation “You will never be a writer.”

My injustice meter swung hard into the red. How could that awful, pretentious, petty despot lay her curse of preordained failure upon someone so young and eager? The witch. She even wore the robes of a witch, or what was with the flowing garments, something borrowed from Stevie Nicks?

Ya’see, there’s this reflex condition that I have. Many people describe the same for themselves. It’s like a component built into a car, so automatic and instinctual. It’s a visceral repulsion upon encountering injustice. Other people have their buttons, something which triggers a deep-rooted rage. Traffic. Unfaithfulness. Cruelty to animals. Injustice is mine. When I smell injustice (a simmering pot of misery spiked with two spoonsful of gall) I must think it and breathe it and speak it. “Look, look what he-she-they-it did! And why? For what reason? It’s not right, it’s not fair! Let the truth come out.” When the injustice involves me directly I usually act the same, though first I give the circumstances a more thorough assessment.

In our faculty preseason game-planning session, Shelnutt started her usual Fiction-As-Spoken-Word jive, and I shot back to the effect that fiction writing may have started with moonlit Neanderthals crouching on rocks and making up yarns, but today, in the modern world, fiction is a written art and a written copy is necessary in order to discuss it, that is, a written copy provided ahead of time so that the reader will have a chance to read the work carefully and reflect upon it before coming to workshop to discuss it.

Kinder, the kinder, diplomatically took my side, and argued the same points, but more eloquently and with a gentler hand. Our fourth colleague, kindly, wily old Dr. Taube, withdrew from the conflict and said little. At one point, Shelnutt grew angry and apropos of nothing asked if my undergraduate degree had come from The Columbia School of Broadcasting.

It was with much strength and power of will, says the Buddha, that I did not stand and turn the table over on her, for I said only, “Well, I don’t know what that is, but let’s return to the point.”

That night, Taube called me at home to say the second day of the confab was canceled. Ms. Shelnutt was unable to attend.

***

I was working on my twenty-second year of so-called formal education. I’ve known many teachers, but I never got to know any teacher as well as I knew Chuck Kinder. In our no-name bar he told me how he smoked weed only when revising a manuscript, never while writing a first draft. He said with his new novel he had almost given up on fiction and was just going to tell the story as it happened. It if turned out to be a novel, fine; a memoir, fine too. He didn’t care what they called it, he just needed to finish it.

I informed him my ex, Joder, had contacted me and wanted to come to Pittsburgh and give it a try. Kinder lowered his voice and spoke over the lip of his beer. He seemed to ignore what I had just said to him. Diane was also moving to Pittsburgh and neither of them knew for sure how that would go. In the meantime, he had been banging the chair of the English department, a handsome, frosted-blonde woman, impeccably and academically coifed and clad. I’d met her. She seemed perfectly nice. I couldn’t imagine her naked on her back, her knees in the air, and Kinder humping her. Yuck, Kinder was thick-shouldered and pot-bellied, the kind of heft Hemingway carried in his late prime, the kind of gut you get from killing, skinning and eating four-legged mammals. In the film of Michael Chabon’s novel Wonder Boys, the woman is played by Frances McDormand, and changed from English department chair into University Chancellor and wife of the English department chair. Michael Douglas must have carbed-up plenty to play Kinder at about the same weight. Or was that only Hollywood trickery?

Talk about trickery, within two weeks Joder was my wife. From there the sex grew less and less ecstatic, until it went away altogether.

Joder was with me, however, when I achieved a literary orgasm in a reading I gave later at an old neighborhood bar near the Cathedral of Learning. The bar was under new management who wanted to tap into the beer budget of average Pitt intellectuals. The bar was refurbished with a new sign on the door: Hemingway’s. With the slick outfitting, the bar also opened a reading series. I think it was a weekly series but don’t quote me on that. I only remember they didn’t ask me to read, and I didn’t ask them. But eventually, after Christmas, they did ask, likely because I was on the air at WQED and known by some to have literary ambitions. For all I know, Kinder suggested me. I just don’t know. Kinder was at Hemingway’s to see me read. So were Chabon and Taube. Shelnutt, a frequent visitor to the series, went absent. I recall who was in the back room of Hemingway’s because the reading turned out to be important to me. I read the first chapter of my novel-in-progress. I started with a wholly ridiculous story about the composer Domenico Scarlatti and his father Alessandro. Their relationship became strained after Domenico chose not to follow his father’s plans for his career. Alessandro wanted his son to pursue sacred music, Domenico felt a strong conviction toward secular music. Then, midway through my fanciful (and funny) story of Great Composers, I stopped and told the audience I wanted to read something that was true. (Like the Scarlatti story wasn’t true, which is not true, it was.) What followed was a pretend obit of my father which I told the audience had been published in the Post-Gazette. For most of the time I was reading the obit, most people seemed to believe me, or anyway they responded as if they did. A spotlight on me as I read while sitting on a three-legged stool, the microphone, on a stand before me, close to my lips, I was in my element at the mike; it was how I spoke, as if at a mike, for I had been speaking into mikes for ten years already at twenty-eight. The obit gradually grew angrier until it was nearly raging, all of it false. I loved my dad and at the time he was still living, healthy and driving an 18-wheel truck. I finished the obit and switched back to the finale of the Scarlatti story, and as I did the audience sat astonished at what I had just told them. When it was done the room exploded with cheers. Look, as a broadcaster I’ve been in positions to receive applause from time to time, hundreds of times. I know what big applause is. This was not just big applause. The cheers in the room went on for minutes, enough time for me to take a bow, go to my booth with Joder and friends, and wait it out as they called for me to take another bow, all the while I asked my friends what was happening. Their faces told me something extraordinary was happening. Nothing like it has ever happened to me since.

Some weeks later, Chabon published a long excerpt from my novel-in-progress in the Pitt literary journal for which he was an editor.

****

Just ahead to a Saturday afternoon. In Pittsburgh, during that time of year, the oppressed Rust Belt Capital could be hot & sticky, or the boutiquery Shady Side sidewalks could be iced over; sometimes only a few days separated these conditions. That Saturday was warm and clear. One afternoon, I had just finished a blunt when Kinder called and invited me to join him and Raymond Carver for a drink at a well-lit bar within the shadow of the ubiquitous Cathedral of Learning.

Serving my six-year sentence in Stillertown, I came to understand the deeper meanings of Guy de Maupassant’s remark that he always had drinks in a bar halfway up the Eiffel Tower: “It’s the only place in Paris where I don’t have to look at it.”

Sitting at a table, drinking with Chuck Kinder and Raymond Carver, I could have been on the Eiffel Tower and not noticed where I was. Carver wasn’t drinking, thanks to Tess. He was on the soda water wagon, enjoying his short bumpy streak across The Blue Skies of American Letters. Kinder, who once put Carver up in his and Diane’s house in SF when they were all drinking to slog-bobbin’ excess, gave Carver a quick redneck-enabler nudge. No, insisted the great minimalist, soda water only. But even if he wasn’t drinking, Kinder was, and so was I. Whiskey and beer.

Carver seemed to me a reticent man, rarely speaking and hardly above a whisper. Mostly he nodded or shook his head to communicate.

Conversation picked up when we were joined by another friend of Kinder’s, a man who, like Chuck, presented to the world the bearded face and faux bluntness of a weekend duck hunter, presumably to mask his prodigious erudition. I didn’t get his name. Soon, others came over and stood by the table to watch.

After another couple of shots, chased by Iron City, I was looped. Alcohol was not my drug. Kinder didn’t look the least bit fazed, though how could I tell? We climbed into someone’s car. Carver and I were squished together in the back seat. (I can tell you what Raymond Carver’s hip felt like, well, pretty much like anyone’s hip, fleshy and bony both.) Next thing I know we were piling out of the car and into Chuck’s home, where a party bubbled. The occasion: Carver’s visit, of course, but also Diane had come from the City by the Bay for the week, part of her transition to the City of Bridges. It was a literary salon, Steel City style. I snaked through the crowd of bright and dimmer domes of contemporary American literature. There were Jayne Anne Philips and Ann Beattie, two writers who inspired and frightened me, I was sure I recognized each, but did not dare approach. Carver remained stuck in the eye of a collegiate hurricane. Was Chabon there? Likely, but I didn’t see him. Maybe out that night singing in his band, The Bats. I looked for the English department head, she who had given head to Chuck. Apparently, a no show.

Kinder introduced me to Diane, an attractive woman at ease in her sun-browned skin and chaotic surroundings. Slender hips, bare shoulders, California tan. She seemed like someone who smiled only when she wanted to. I gave her my litmus test: I’d fuck her.

Soon I found myself with a beer in hand, sitting in a small room (a sitting room?) with Kinder and about four or five other young Hemingways. He was holding court, as one does when one is the big dog writer in the room. Were we all part of his coterie?

After a few minutes of witty quips and vigorous seat-swapping, I found myself sitting next to Kinder, close enough to whisper to him, and in a whisper I asked, “How’s it going with, you know, that thing you told me about?”

“What thing?” said Kinder.

“You know, you and –“

Kinder stiffened. “Not here, not in my home.”

Almost immediately, Kinder lumbered to his feet. I recognized my drunken mistake, but too late. Kinder was on his way to the door, kibitzing with other fledgling sycophants as he went. After a moment I went after him, hoping to apologize, but he’d disappeared within the bright kaleidoscopic light of American literati. Was that Tobias Wolff who just squeezed past? After several minutes of threading through the crowd I found Kinder, laughing like a sweaty good ol’ boy from coal country, his hand on another man’s shoulder. I put myself more or less in front of him. Surely he could see me, see my pleading eyes, but he ignored me and a few seconds later he brushed past me as if I was a potted palm from La La Land, my branch in his way.

Naturally, I left the party as fast as I could find the door. Wait a minute, there’s Richard Ford, isn’t it? I nixed the bus and walked home over Pittsburgh’s rolling hills, an hour in the dark, enough time to stew in my mistake and imagine the consequences.

What if the situation was reversed? What would I do? I would laugh it off, I reassured myself. Why? Because that’s what I always try to do first. Had I so violated the writer-hunter’s code that I should be shunned? Years later, during the deluge that would end in my divorce, I would feel the same pressure that Kinder must have felt when I raised the subject of his adultery, while his wife could at any moment come through the door. How stupid of me.

But think of this: If I was so careless that I talked with a man about screwing another woman while my wife was living far away, then either I’m a stoned fool or I believe the man is a good friend. Or both.

Well, there you have my answer. I was Chuck’s good friend. A drunk friend on that night, but a good friend always, and I could not have been persuaded otherwise, for I, to coin a phrase, felt it in my heart. I rested easy. I knew that if it was me I would give my good friend a second chance, and maybe a friendly pissed off shove.

Dad tells a story of the best man at his wedding, call him Wayne. Upon returning from Europe at the end of WWII, Bob was invited by Wayne to a Christmas party at his house, where the giddy guests loaded up the U.S. Marine return-from-the-war with drink after drink. Bob grew unsteady and fell onto the table and onto Wayne’s model ship, which was made of tiny pieces of wood and which Wayne must have spent untold hours painstakingly building. Down she goes, sunk in the deep waters of friendship. Wayne, Best Man Wayne, never spoke to Dad again, despite Dad’s many overtures. He wondered why till the end of his life. How could a model ship destroy the bond between groom and best man?

I had come too near to Kinder. In my drunkenness, drunk on beer and whiskey, but also drunk with the glittering literati, I, polite boy from L.A., stood among it all feeling both in and of this group of brilliant people. In my drunkenness, I had mistaken this glorious achievement of mine for acceptance into the exclusive life of literature. Then at my first social event I toss a raw egg to the host and it breaks in his palms. I confess, I did it, in my drunkenness.

The weekend ran its sloshy course and on Monday I dropped by Dr. Taube’s office-nest, a place where comfort and challenge were served in equal parts. I came often to this paper-feathered sanctuary; Taube was also on my thesis committee. After we’d talked a quarter-hour or more (rather, he talked as I listened) he told me that Chuck had come to see him and said he had to resign from the committee.

Had to resign? I asked why, but Taube evaded the question with the tactful skill of a lifelong academic. He said he would be willing to step up to head the committee, if that’s what I wanted.

Never mind how the whole thesis business went for me. Just to get it out of the way: It worked out, not on schedule and without Kinder, but it worked out.

Weeks passed. Bruce Dobler, who had been teaching “brain-addled undergrads” for six years at Pitt, put himself up for tenure. He was competing for a single tenured slot with Eve Shelnutt. Bruce asked for my help. I had never taken a class with Bruce, unless you count the three-day orientational class on teaching and anal sex. I had reason enough to help the pasty-faced Dobler with his tenure quest, if it got in Shelnutt’s way, but how could I endorse Dobler? I did what I thought was the honest thing. Leaving Dobler out entirely, I wrote a rant about Shelnutt, and included my account of an incident that took place on the first night I attended her workshop. (Hers was the only grad-level workshop offered that semester.) She asked the group of us, about twelve, who would like to volunteer to read a story aloud (since no one would be receiving a paper copy of the story). Right away a hand shot up. It was Shelnutt’s lead WMU Bronco, Mark Shelton, a man young enough to be her son, who in a few months would become her husband. Shelnutt gave him the green light. The unwashed mutt stuck his nose down nearly to the polyethylene surface of his desk chair and read in a murmured monotone. On the other side of the room, I could make out only about every fourth sentence.

Shelnutt was subtler and more elliptical in her prose than in her pedagogy. Shelton finished his dreary recitation, and immediately Shelnutt pointed at me and called for my response.

I refused to allow myself to be embarrassed. “I don’t have a response yet, not until I have a chance to read the story. I couldn’t really hear it. What was the title again?”

Shelnutt glared at me with the parched contempt of a reptile, and then proceeded to call on one-two-three Kalamazoo asses, each of whom sounded like he’d already read and discussed this latest of Mark Shelton’s Adventures in Introversion several times. I did not return to the class and withdrew.

I sent my Shelnutt rant to the tenure committee. It also included an account of the incident with my A-minus student Christine, crushed by Shelnutt’s absolutist hammer. Many days passed. I had my head back into writing and teaching, and forgot about my letter to the committee, or at most I thought it had probably been read by one person, who put it away with all such angry and wildly inappropriate correspondence. Then one late afternoon, I was approaching The Cathedral of Learning and happened to fall in step with Madame English Department Head, that is, she caught up with me, and we fell in step. She was prettier than Frances McDormand, perhaps ten years my senior.

“I wanted to thank you, Dennis, and tell you that your letter provoked a lot of discussion among the committee.”

For a moment I had to think how she knew my name. I stopped and looked in her eyes. This time I could imagine her writhing beneath Kinder. I thought she’d be too much woman for me. “Well, I guess that’s good. I only tried to tell the truth.”

“And we appreciate that you told the truth.”

I restrained myself from throwing more anecdotal wood on the fire I’d apparently started, though I had plenty still stockpiled. I muzzled myself to keep from asking if Kinder was on the committee and blurting out that I knew about her affair with Chuck. I held back the urge to put my hands on her shoulders, pull her to my chest and kiss her with lust and anger and frustration and heartache.

Shelnutt did not get her tenure. Neither did Dobler. But Shelnutt got her revenge. The English novelist Angus Wilson came to Pitt to serve three months as writer-in-residence. The salty author of Anglo-Saxon Attitudes was always accompanied by his secretary-amanuensis, driver-dinner companion, Tony, who was two-decades younger than the wizened CBE whose masterpieces lay a quarter-century behind him. The former “famous homosexual” looked every one of his seventy years, with several more years carved into his face, but when I met him and Tony at brunch, and during the few times I observed him in seminars, Sir Angus was always laughing, or right on the verge of laughing. He looked like he was having a blast, and was charmed by Pittsburgh. Relating the moment when he and Tony discovered the Black Angus, a swank steakhouse I’d walked past many times but never entered, Angus Wilson broke into a cackling squeal. “The Black Angus!” British humor, I guess.

As writer-in-residence, Sir Angus held the privilege of selecting two writers to read at the Pitt Writing Program’s grand year-end ballyhoo. It was the Pitt Writing Program’s highest annual honor. Shelnutt was administrating the event.

Beyond its artistic merit, Wilson’s The Middle Age of Mrs. Eliot also represents one of the first novels, or maybe the first, to depict a gay man moving into a nursing home/convalescent hospital/assisted care facility, where his partner is dying, and caring for him to the end.

The genius behind Mrs. Eliot selected an old dog of a man, Roger, to read his own work at the big reading. Roger had lived in Pittsburgh all his life and wrote dreadful mysteries. He rarely spoke in workshops. He was unwaveringly appreciative of everything submitted, and never engaged in conflict. You could say anything about his work, good or bad, fawning or scathing, and he wouldn’t flinch. There was something about Roger that said he had seen the Edge of himself and his writing came from there. I thought his work improved with every manuscript. Sir Angus also selected me.

With all of Shelnutt’s covey of obedient turds shut out, she abruptly shut down the event entirely.

At the end of my two-years of T-Fellowing, I was surprised by an offer that came from the tall and somewhat remote poet Ed Ochester, who ran the Pitt Writing Program. He asked if I’d like to join the faculty as a junior member, that summer and fall, for starters. Without any other prospects, I declined.

In the fall, on the eve of the annual Pitt Writers’ Conference, I published in the Post-Gazette a screed on writing programs, onto which was slapped the headline “Does a writing program produce writers?” In the piece, I quote Kinder, not by name, who in a workshop exclaimed with the hushed passion of a duck hunter in a boat blind: “One of the reasons Hemingway was in Paris and stayed in Paris was that he met people like Stein and others who taught him how to work, how to write.”

Pitt’s Writing Program came in for my worst abuse. “The organizers of the Pitt Writers’ Conference, congratulating themselves, promoting each other, boast that the conference will be three days filled with a dozen writers and editors, all talking about writing, publishing, and subsisting as a writer. Pitt’s Writing Program is the nation’s oldest undergraduate writing program in the country, dating from 1932. Has Pitt’s Writing Program produced many writers of enduring national value? Name one.”

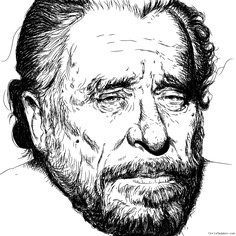

There would soon be one, but not on that day, the day of the Pitt Writers’ Conference, which just the day before I had disparaged in the city’s paper of record, and which would one day be lampooned in Wonder Boys by Pitt’s first writer of enduring national value. I arrived at the conference prepared to look and listen. I was also prepared to debate, or to be insulted. I wasn’t one to snipe and hide. I felt I was prepared for anything, but I was not prepared to encounter Kinder within steps after entering the building. Maybe I had envisioned it as more of a gun fight in the dusty street of Dodge City, but now there he was, leaning on a banister, looking out at the theater, or lecture hall, or whatever they called it. There was a stage; Kinder’s gaze was fixed down on it. I decided I would not go unseen by him. I stepped to the banister and stood, facing him, within four feet. I braced myself to hear what the man had to say to me, if he had anything to say to me. If he chose not to speak, I would step away, out of respect for him, but I was there now and would offer him the option. I stared at Chuck’s ravaged face, in his eyes.

I’d seen worse. Bukowski’s face. I used to play the horses with Bukowski sometimes at Santa Anita, along with a continuously changing gaggle of druggies, whores, and peach-fuzz kids like me fascinated with the slimy underbelly and barely literate enough to read Bukowski’s simple, brutal depictions of it. He called us

blazing bastard fools …

soft lumps of humanity …

still

in the shadow of

the

Mother

you

have never

bargained with

the Beast

you have never

tasted

the full flavor of

Hell

(from “see here, you”)

Bukowski’s face was a spoiled melon. It revealed the lines of a writer who had earned every dime, and sometimes it was only dimes he earned. Whereas, Kinder’s face concealed more than it revealed. His pale skin looked unhealthy. His heft amplified the struggle it took to breathe heavily. I inched closer. If Kinder could not see me now, he had no business driving.

“Don’t you see me?”

He saw me, all right. He said nothing. He stood right there, silent as a buffalo shot through the head with an arrow. Like some goddamn dead buffalo. I turned away and walked out, fleeing.

*

Unmoored from the university, all ships scatter in wild directions. Shelnutt and Shelton married. Tenureless, Shelnutt packed up and moved on. She landed at Ohio University, alma mater to former Today co-host Matt Lauer, and baseball Hall-of-Famer Mike Schmidt. Later, I heard Shelnutt and Shelton divorced.

Despite failing in his tenure attempt, not his first try, Dobler stayed at Pitt. His family was rooted there, and his wife Pat was a rising Carnegie-Mellon poet. One day, Dobler would leave them and move to El Paso with his young girlfriend. He’s now dead.

Chabon was again editor for the Pitt lit mag and, in the same chummily deferential way, he asked me for a second chunk of my novel-in-progress, He also told me he wanted to get into a MFA program and asked if I would write to one of my former professors at U.C., Irvine, which I did, to both Oakley Hall and Don Heiney, the only two professors in the program. They created it together. I understand Chuck Kinder wrote a similar letter on Michael’s behalf to Stanford, his alma mater of reckless excess, though it went for naught. Maybe my letter scored points. I hoped so. I had come to like Michael. I wanted to help him. Irvine had been good for me. Only six lucky contestants were admitted each year into UCI’s famed program. That year, Michael was one of them. Legend has it, it was Heiney who, without telling Chabon, gave a copy of the manuscript for The Mysteries of Pittsburgh to his NY mega-agent, Virginia Barber, whereupon a bidding war ensued, and Chabon was offered more money than he would have dared ask for. His career had lift-off.

By then, I had left Pittsburgh to run a Baltimore radio station. After Michael hit the big time with Mysteries, and especially after winning the Pulitzer, I felt uneasy about getting too close and looking as if I was trying to ease my way into his spotlight. Wordlessly, I disappeared from his horizon, not that my presence in his life was ever very present in the first place. But then I read, in The New York Review of Books, Michael wrote I was a great teacher. What did he mean? What was so great? My antics in the classroom? I had a hat full of tricks, or was I great because I was the first person in a position of minor authority in this exclusive realm called fiction writing to recognize his work as exceptional, and to recognize him as existing in an even more exclusive and remote, weird and miraculous realm, the name of which is whispered by those who worship the word?

Chabon did the same for Shelnutt and Kinder, called them great, whose workshops he took after mine. During a return visit to Pitt, evidentially brought about by Kinder, Michael answered a student’s question about the best advice he’d received at Pitt by saying, “It was from Dennis Bartel, a teacher I had here. He said, ‘If you want to write a novel, you’re going to have to sit on your ass.’ At the time I said, ‘Yeah, whatever dude.’”

Fifteen years later, after another long ride writing for my living, I was back in radio again, because radio paid me three times more, this time at WGMS, which promoted itself as “The Most Listened to Classical Station in America.” I don’t have the Arbitrons to break it down, but WGMS was a top-five station in D.C., saturated the Washington Metro Area, and raked in advertising dollars for high-end products by playing Beethoven and Mozart. I was your friendly DJ, evenings, which left days free for me to write. A literary agent signed me to a contract and chose to try the market first with my collection of stories, instead of my “idiosyncratic” novel. The agent persisted in telling me how essential it was that someone “of note” must blurb the back of the book. “Isn’t there a name writer in your past? A teacher maybe?”

I mentioned Michael. We hadn’t spoken in a long time, but there’d been no falling out between us. Polite e-mails were exchanged, my manuscript was sent to Chabon, and he sent his blurb to the agent. It was generous, no doubt more than the slender book deserved, and more than I deserved. I wondered if his blurb was less a professional endorsement and more a personal favor? Whatever, dude. I laughed it off and remained grateful for his willingness to be bothered with it at all.

As for Kinder, I hear he’s retired from Pitt and now lives in Key Largo, with Diane, who cares for him. May he live long.