Charles Bukowski

Feverish with Climbing Broken Ladders

Dennis Bartel

(Written upon the death of Charles Bukowski, March 1994, and published in The Baltimore Sun.)

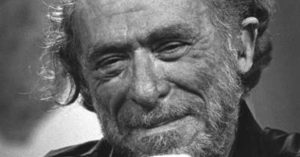

I knew Charles Bukowski. We bet the horses together sometimes. I can still see him, in an old undershirt and army surplus pants, his face like a spoiled melon, upturned, watching the tote.

I knew Charles Bukowski. We bet the horses together sometimes. I can still see him, in an old undershirt and army surplus pants, his face like a spoiled melon, upturned, watching the tote.

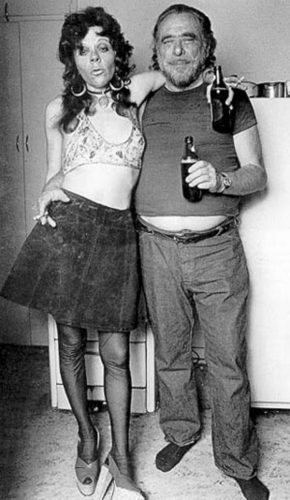

This was many years ago, back in L.A., before the movie Barfly, before most of the 40 books: Notes of a Dirty Man; Flower, Fist and Bestial Wail; Erections, Ejaculations, Exhibitions; and General Tales of Ordinary Madness. The cult around Bukowski was still small back then, made up of druggies, whores and other outcasts, and peach-fuzz kids like me fascinated with the slimy underbelly and barely literate enough to read Bukowski’s simple, brutal picture of it.

Now Bukowski has died a hard death at 73, leukemia and pneumonia, disappearing in the dead of winter. He’s become his admirers, or, as he said himself, “become just another dead poet.” Word of his death was all over the mass media, as word of his books never was.

Now Bukowski has died a hard death at 73, leukemia and pneumonia, disappearing in the dead of winter. He’s become his admirers, or, as he said himself, “become just another dead poet.” Word of his death was all over the mass media, as word of his books never was.

But no one in the mass media, while noting the passing of this “street poet,” this “poet whose subject was excess,” has dared to quote any of the poet’s poems. This may be because it is difficult to quote a passage of Bukowski without including an obscenity, or several. But it can be done.

It is Saturday and hot

And the faces of greed rushing past

Pinched and dried and impossible

Want to make me kneel amongst the lilies and pray

But instead I go to a bar

Bukowski’s favorite composer was Beethoven. At least that’s what he told me. To someone else he might have said Mozart or Schumann or Stravinsky. (Never Tchaikovsky.) He called Beethoven “just a fat beer-drinking German.” In Beethoven he saw heroic struggle as it really is – isolated, tawdry, profane, absurd, heavy with the oppression of everyday banality, and heroic all the same.

as I went past

Beethoven said, I got a couple of

Babes lined up for tonight;

Don’t injure anything

You might need later . . .

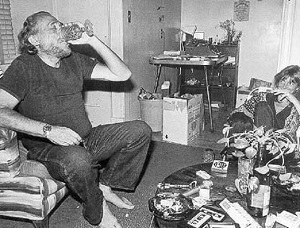

Like Beethoven, Bukowski could rarely be bothered with matters of housework or hygiene. Let me try to put it as he might have put it: Bukowski, like the whole world around him, was filthy. I remember in his bathroom, where many of his poems take place, the sink was covered with snippets of black beard hairs that Bukowski, standing wine-soaked before the mirror, had clipped over the past few months.

Like Beethoven, Bukowski could rarely be bothered with matters of housework or hygiene. Let me try to put it as he might have put it: Bukowski, like the whole world around him, was filthy. I remember in his bathroom, where many of his poems take place, the sink was covered with snippets of black beard hairs that Bukowski, standing wine-soaked before the mirror, had clipped over the past few months.

Back then, Bukowski’s world was an aberration to me, as I came to it from my tidy suburban home. Likewise, Bukowski himself was an aberration, a man, as he said, “not grounded in the classics” (though in fact he was), playing “the screw game” and wallowing with drunkards, losers and criminals, yet somehow now and then capturing in his rot-gut verse a flicker of precious beauty, hard won.

down at the end of the bar

he used to bum

drinks, now he is a balding man and

I lean close:

You are the finest poet of our age, you are the

Only one that everybody

Understands . . .

Now these many years later, I live in South Baltimore where I think Bukowski would have felt at home. Street girls elbow one another for working room on the sidewalk. (“Whores are always rolling down their hose,” he wrote.) Soggy-eyed panhandlers curl up in the nooks between bars. Patrons of two local drug houses keep four corner pay phones hopping at all hours, though, as Bukowski often did from pay phones, they’re probably not calling their bookies.

And now that I’m closer to the kind of squalor Bukowski lived in, the poignancy of his vision becomes clearer to me.

If you decide,

Take us

Who stand and smoke and glower;

We are rusty with sadness and feverish

With climbing broken ladders.

Take us:

We were never children like your children.

We do not understand love songs.

Listen to Charles Bukowski read his poem “Bluebird.”

DJB takes us inside a Baltimore soup kitchen and outside onto the streets to hear from its patrons. Click below to hear this iconic radio documentary.