The Real Davy Crockett

Notes from Eastern Tennessee

Dennis Bartel

Dear Charlie,

Driving east, cross TN. We’ve stuck to the blue roads, which are littered with dead critters – mostly rabbits and rodents, a few deer – the two-lane highway crowded with mobile thoroughbred stalls. All day the sky is pewter and rainy. Greenest state in the land of the free. And what is the cash crop that brings TN its most green? Why, jabooby, of course. Good Southern name, an’t it? Seeing as we’re down here in the grafa bag of America, we – Erin and I – blow keef all the way cross the state. I suppose that’s how we decide to make the considerable detour to find the Crockett birthplace. It’s after dark when we emerge from the forest and arrive in the nearest big town, Johnson City. We check into a Ramada, flip on ESPN, the traveler’s friend, and fall asleep wasted, glad, anticipatory.

I admit, Davy Crockett was my first TV perturbation. I was three. Interesting, Crockett was likewise for Erin, except she first saw Crockett in reruns. She was a tomboy under a coonskin cap, an authentic one from Frontierland. We were fated to fall in love twenty-five years later.

Next morning is sunshiny. We set out early, driving 25 miles into the misty forest and farmland. Now that the trees have grown back, recovering from deforestation, this side of TN looks like land untouched by the carbon hands of corruption. Endless green canopies evoke plantation days. A single, official brown sign points the way to the Davy Crockett Birthplace State Park. We turn off the big road and wind down a path that grows gritty and narrows to the width of our little red car. We stop about a mile short, agreeing it best to approach on foot. Nothing is said of Disney as we follow the cattle-lined banks of the Nolichucky River and enter the park in late morning, 66 acres, few visitors. We see one campsite. The first Disney legend to be debunked is this business of a mountaintop in Tennessee. Crockett was born in a valley, west of the Appalachian Mountains, in the territory of Franklin, which had recently broken away from North Carolina.

Crockett’s father, John Crockett, named after his father, ran a tavern on the stage road from Knoxville to Abingdon. John dabbled in local politics despite his impoverished plight in life, and supported both Franklin’s succession and the new independent territory’s attempt to enter the Union as the 14th U.S. state. John Crockett was disappointed when Franklin came up a few votes short in Congress, but it would hardly be his greatest disappointment.

Two years later, August 17, in a one-room log cabin, 30-year-old Rebecca Crockett gave birth to her sixth of what would be nine children, David, named after his paternal grandfather David “the Elder” Crockett (b.1729, Pennsylvania) who at 48 stood by the side of his wife Elizabeth, 37, as both were murdered by Creeks and Chickamauga Cherokees; the Elder was son of William David Crockett (1709, New York City) the first of the Crockett clan to be born in North America, and son of Joseph Louis Crockett (1676, Ireland) who immigrated to the New World, and son of Antoine de Saussure Peronette de Crocketagne (1643, France) who served at Versailles under King Louis XIV in command of an court security team; upon moving to Ireland, Antoine de Saussure Peronette de Crocketagne changed the family name to Crockett. David and his older siblings – Margaret Catharine (c1777), Nathan (1778), William (1780), Aaron (1782), James Patterson (1784), John (1787), Elizabeth (1788), and Rebecca (1796) – thus became green grass members of America’s first native-born generation. By 1841, all nine Crockett kids, plus mom and pop Crockett, were deceased.

At age 12, David was hired out as an indentured servant to pay off his father’s debts. Jacob Siler bought David for a year; he had cows to move to Rockbridge county, Virginia. Crockett proved himself a good wrangler, taking care of the remuda, where the drive’s herd of work horses were kept. Crockett issued loving care to every equine, both the saddled horses ridden by the swing, flank, and drag riders, and the near-nags who spent their days hitched to the wagon, no matter if they were blistering hot or drenched in rain cold as creekwater. Crockett also took care of the horses the point rider, that is, Siler, chose from to ride that day. Crockett had the herd ready before sunrise. He knew how each horse was faring. David also rustled firewood for the cook, things like that. Once the first cattle drive was successfully completed, the posse of cowboys rested before the next run, and within a few days, David declared he was going home. Siler recognized what he saw in Crockett, and didn’t want to lose him, especially only three months into the boy’s contract. He insisted David stay and got a stubborn No in return. Siler wanted to know, had he been mistreated? No. Had he not been paid? No. After much argument with the teenager, Siler attempted to keep him from leaving by force. What that meant exactly Crockett did not tell, but we learn from David he had to fight Siler to escape.

Crockett returned home. His father, none too pleased with his son breaking his contract with Siler, put him into a local school, where he received his first and only formal education. Crockett recalled, “I went four days, and had just began to learn my letters a little, when I had an unfortunate falling out with one of the scholars – a boy much larger and older than myself.” David ambushed the bully and gave him a thrashing, but afterward he was afraid to return to school. John Crockett happened to be drunk when he learned his son had been ditching, and, depending on who you believe, either whipped his son terribly, or tried to and David was too good a dodger and ran away from home, not for a day or a week or a month, not for a year, but for thirty months. The young Crockett earned money as a wagoner (delivering goods by wagon) a common day laborer, a farmhand, a teamster in Garrardstown, West Virginia, a cattleman in Front Royal, Virginia, and an apprentice to a Christiansburg, Virginia, hat-maker. Crockett would take any job available. He was good with his hands. Eventually, he returned home to welcome arms from all, even his father, who promptly contracted him out to two creditors. Within a year David paid off John Crockett’s debts of $76. Having done his duty by his family, he was free to leave if he chose, which, after a few months, Crockett did.

As anyone might guess, the story of Crockett has been besieged by myth, Disney, and many years of the scurrilous Nashville Crockett Almanac, but Erin tells me she once, in college, witnessed a seething attack on another front. The attacker, an academician with an agenda, claimed the Crockett myth first flourished in the 1830s because it provided an outlet for hostility and frustration for young white males just reaching the height of their fear of masturbation. It was a time, the prof said, of “jingoism and racism,” and Crockett was their man.

We prefer to think of Crockett as holding a place in American lore like no other man. Benevolent, with honesty in his genes, Crockett’s most famous utterance stands among the greatest for plain and simple American wisdom: Be sure you’re right, then go ahead. Actually, with the early 19th century verse restored, it reads: Be sure, always, you’re right, then go ahead. And restoration of the truth in matters of Crockett is the pledge of this state park. The small and tidy Crockett Museum does not sell trinkets and postcards, only a few legit history books published by the University of Tennessee, including a facsimile edition of Crockett’s autobiography. Among the many wrongs the museum rights: Crockett was not six foot four in his stocking feet, but a stocky 5’9”. He did not ride a streak of lightning. He did not drink up the Gulf of Mexico.

We learn that Crockett, in the autumn of 1805, after two spasmodic and doomed engagements to other women, courted Mary Finley (known as “Polly”) for over six months before proposing in 1806, only to meet unexpected resistance from Polly’s mother. Crockett declared he was going to marry Polly whatever Mrs. Finley’s feelings about him not being a suitable husband and all. Crockett declared the wedding might rightly take place at the Finley home or it could be conducted somewhere else. Crockett contracted a Jefferson County Justice of the Peace and three days before his 20th birthday, he rode with friends and family to pick up Polly and take her away into matrimony. As Mrs. Finely stood back, Polly’s father pleaded with Crockett to hold the wedding with them, there, in their home. Crockett relented on the condition that Finley’s wife apologize for her harsh treatment him.

The Crocketts settled on a few acres near the Finleys. A year later, Davy & Polly became parents to John Wesley, named after Crockett’s father and presumably also after the founder of Methodism, as there was no prior Wesley in the Crockett family tree, dating to 1643. Two years hence, Crockett and Poly welcomed baby William, named after Davy’s uncle on his father’s side.

A man of many trades, Crockett made a living with a diverse mix of trades. He farmed and made gunpowder. He built wood barrels. He once nearly drowned when his boats, carrying barrel staves, wrecked on the Mississippi River. Crockett had other passing businesses, most famously as a professional hunter, providing food, pelts, and oil to settlers in the region. Davy was widely known as the best black bear stalker in Tennessee. He cleared many a valley of bears for settlements, the citizens of which honored him as a hero for his life-protecting work. Crockett was happy to accept the honors and hoist a mug with those who honored him.

After a faction of Creek Indians, “Red Sticks,” attacked settlers at Fort Mims, near Mobile, Mississippi, killing dozens, Crockett (27), volunteered for a ninety-day stint with Andrew Jackson’s militia as a scout and wild game hunter. In November, Crockett was present at the massacre at the Creek village of Tallussahatchee, home to the Red Sticks. I can find neither proof nor suggestion that Crockett acted as any more than an outrider. He came home to Polly, John Wesley and William before the Christmas holidays had ended. Next September, Crockett was a soldier again in the Creek War, serving as a 3rd Sergeant in Jackson’s advance on the Florida panhandle in an attempt to cut off the British army’s covert supply chain to the Pensacola tribe. Their mission: Flush out the Muskogean-speaking Indians from the swamps.

He arrived back in Tennessee to find Polly in good health, having given birth to a girl, Margaret. Davy rejoiced. The Crocketts were five. But Paradise was fleeting for Crockett. Come summer, Polly fell ill and perished. Now 29, Crockett experienced his first heartbreak, but had no time to suffer. At home were three children, John Wesley (age 8), William Finley (6), and the infant Margaret Finley, “Polly,” with no one to care for them. Davy set to work immediately. He moved with his shocked children to Franklin County, where he was surprisingly popular with fellow Tennesseans, due to his service under General Jackson. On the strength of this renown, Davy got himself elected a Lieutenant in the 32nd Militia Regiment of Franklin County. A year after his wife’s death, Crockett married a widowed mother, Elizabeth Patton, whose children were George and Margaret Ann. He was appointed a Lawrence County Justice of the Peace, and elected as Colonel in the 57th Militia Regiment. In 1821, Crockett campaigned two months for a seat in the Tennessee state legislature. His opponent was Jackson’s nephew-in-law William Edward Butler. Each time he spoke on the campaign trail, Crockett had more to say about public land policy and the rights of poor settlers, men like his father. Crockett honed his oratory skills in the legislature, pleading the case of the impoverished farmer. In that same election, which sent Jackson to the United States Senate, Crockett supported Jackson’s opponent John Williams. Two years later, Crockett was re-elected as a Tennessee legislator.

It turned out, Davy was a family man. He wanted to spend more time with his children, so when his second Tennessee legislative session ended, he resigned as commissioner and stepped down from the militia. Soon he, his son John Wesley, and Davy’s friend Abram Henry, set out to explore the Obion River country, looking for a new home. A few months later, Crockett moved his family there.

“Brace yourself,” says Erin, skimming a scholarly tome. “He didn’t wear a coonskin cap.”

Indeed, we learn that while he was a renowned hunter, Crockett was generally averse to wearing the skin of animals. He wore a crushed felt hat. He did own a coonskin cap, but wore it only for the rare winter hunt.

At forty-one, after one failed campaign, Crockett won a seat in the United States House of Representatives, defeating two other Tennessee Colonels, William Arnold and Adam Alexander. As a Congressman, he wore a stovepipe hat that made him look like a rube in disguise. He played up this image in Washington. Quoth Crockett on the floor of the House of Representatives: “I’m half-alligator, half-horse. My father can whip any man here, and I can whip my father.” The next year, Crockett’s unwitting political father Andrew Jackson became U.S. President.

As fellow Tennesseans and fellow soldiers, Jackson and Crockett had many common bonds, but Davy soon revealed his dissention from Jackson’s proposal to get Federal funds to farmers and settlers by depositing the funds in local banks to distribute locally. Crockett disagreed. He said Federal funds should be distributed by Federal hands. After years of advocating for local farmers and settlers, Crockett didn’t want the funds filtered (that is, mishandled) through local banks. History has shown Crockett right. Jackson’s deposit scheme led to the first American economic depression. Even casual students of Old Hickory know how he responded to Crockett’s opposition, with anger and plots of revenge. (Jackson reportedly said his greatest regret of his presidency was “I didn’t shoot Henry Clay and I didn’t hang John C. Calhoun.”) Perhaps President Jackson had too many other issues to handle before seeking vengeance over a fellow legislator, for back in western Tennessee, Crockett was re-elected to Congress.

Crockett’s next fork in the road which took him astray from Jackson proved who held the power and who was a Congressman. Davy fought the President’s “Indian Removal Bill.” He was the only member of the Tennessee delegation to do so, and evidentially one of only a few Tennesseans to approve of his opposition. “I believed it was a wicked, unjust measure and that I should go against it,” Crockett wrote, “let the cost against me be what it might.” (One who did approve, Cherokee Chief John Ross, thanked Crockett in a letter.) The cost was Davy’s seat in Congress. Jackson, hoping to kill Crockett’s political career in Washington, backed Davy’s opponent, giving his full endorsement to a lawyer educated in England, William Fitzgerald, former TN state legislator with Crockett, and more recently Tennessee Attorney General. In a close election, Crockett fell short. We read the words of a scholar: “Crockett was true to Jacksonian principles after Jackson himself had given them up.”

In 1833, Crockett was back on the campaign trail, rising from the ashes. He turned the tables on Fitzgerald, handing him a humiliating electoral defeat. Davy’s second term on Capitol Hill was no more productive than his first. He failed to pass anything, not one bill, though he did introduce a resolution to abolish the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, objecting to public funds benefiting the sons of wealthy families. About the only thing Crockett got done in his final term was to write his autobiography, with Thomas Chilton, a Kentucky Congressman.

Voted out of office, Crockett took his book east and was greeted by large, enthusiastic crowds. Upon returning home, he said to a reporter, “I told the people of my district that I would serve them faithfully as I had done; but if not, they might go to hell and I would go to Texas.” He went to Texas to stake out a homestead. With Elizabeth, Crockett had fathered a son (Robert) and two daughters (Rebecca Elvira and Matilda). Alas, the Alamo.

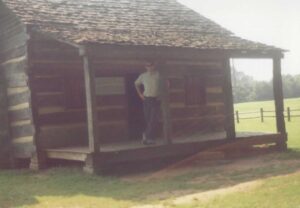

But it’s not Crockett’s death that is marked here at the park, it’s his birth, the start of a life lived nobly according to his time. On the well-kept grounds is a modest monument with tokens of respect from all 50 states. And there is the Crockett cabin, or a reproduction, the original crumbled with time. True to the best American lore, it is a humble abode. Charlie, I swear it has fewer square feet than your kitchen, and it has no kitchen, just a room.

But then, David Crockett was never one for the gilded things of this world: “Most of authors seek fame,” he wrote in his autobiography, “but I seek justice – a holier impulse than ever entered into the ambitious struggles of the votaries of that fickle, flirting goddess.”

“I’m glad we came,” says Erin. We hike back to the car, then drive back into the park, and set up camp on the banks of the Nolichucky, within sight of the cabin in the middle distance. We share a stick of gage and salute Crockett and his reemerging humanity. In the morning, we awake to the sound of mooing cows. Hi 2 K.

Dennis

Notes: Originally published August 14, 1991, the 185th wedding anniversary of Davy & Polly Crockett, in the newsweekly In Pittsburgh. Charlie is Charlie Humphrey, then editor of IP. K was Kay, the grandmotherly cheerful, longtime receptionist at IP.

Notes: Originally published August 14, 1991, the 185th wedding anniversary of Davy & Polly Crockett, in the newsweekly In Pittsburgh. Charlie is Charlie Humphrey, then editor of IP. K was Kay, the grandmotherly cheerful, longtime receptionist at IP.