An Interview with Eugene Ionesco

Dennis Bartel

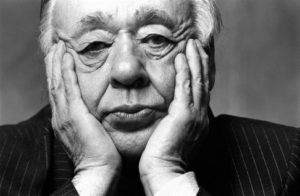

Doomsayers have often served to awaken society to a more acute awareness of the times. Certainly the distinguished French playwright, Eugene Ionesco, has played this role. But unlike other avant-garde artists, instead of merely announcing the eventual destruction of humankind, Ionesco seems to have had a higher purpose. Jacobsen and Mueller write, “Ionesco, amid and despite a welter of contradiction, sees his calling in part as that of summoning mankind back to its humanity.” Through the staggering pessimism of Ionesco’s plays, man may come to know mankind through the distorted lens of love and compassion. Indicative of this calling is Ionesco’s play Rhinoceros. The 70-year-old playwright was recently in Los Angeles to participate in the direction of his landmark work. The interview was translated from the French by Margaret Coppernoll.

Doomsayers have often served to awaken society to a more acute awareness of the times. Certainly the distinguished French playwright, Eugene Ionesco, has played this role. But unlike other avant-garde artists, instead of merely announcing the eventual destruction of humankind, Ionesco seems to have had a higher purpose. Jacobsen and Mueller write, “Ionesco, amid and despite a welter of contradiction, sees his calling in part as that of summoning mankind back to its humanity.” Through the staggering pessimism of Ionesco’s plays, man may come to know mankind through the distorted lens of love and compassion. Indicative of this calling is Ionesco’s play Rhinoceros. The 70-year-old playwright was recently in Los Angeles to participate in the direction of his landmark work. The interview was translated from the French by Margaret Coppernoll.

Autumn 1979, on the campus of the University of Southern California

DB. Rhinoceros was written, I understand, as a reaction to Nazism.

EI. Exactly correct.

DB. Have your thoughts about the play changed after so many years?

EI. When I was very young in Europe I was witness to the rise of Nazism and its triumph, with its corollary racism, collectivism, antisemitism and the supremacy of the state over the individual. I was witness to all of these when I was very young. The experience of Berenger is my experience. I asked myself if it was possible for me to be right against the rest of the world or against a great majority of the people. Nazism was very well founded on economical ideologies, biological ideologies and so on. Since I did not have the intellectual experience necessary, I wondered if I was right in being against them. As for Rhinoceros, I think its significance, or sense and true meaning, has expanded considerably. I ask the question: What does it mean for people today? Rhinoceritis? It has become the criticism of conformism, but especially and precisely a criticism of totalitarianism, or totalitarian doctrines and collectivism. This play has become very contemporary because today there are Berengers everywhere in the world who rise up against all these ideas of collectivism and these outrageous ideologies. There are many people we could use as examples. Martin Luther King, and especially the Russians like Solzhenitsyn . . . these men resisted collectivism and conformism.

DB. One criticism of Rhinoceros has been that while you’ve attacked conformist ideologies what is left is a vacuum, that is, Berenger never gives a hint of what inspired his resistance. I should say, I’m not looking for any one idea or source of strength that has aided this man.

EI. First of all, a reaction, a human reaction, which is very difficult to explain. It was a refusal on his part to accept or to participate in or belong to this certain ideological collectivism. For example, he cannot stand racism. He doesn’t believe in a class system. He doesn’t believe in a superior race and slaves. It was against this that Berenger wanted to defend himself. He wanted to defend the rights of man. You can see it has become a contemporary question. It has become, unfortunately, a problem again. Every time the state has supremacy it becomes a catastrophe. When the state takes over, the rights of man suffer. In any case, Berenger is justified because of the circumstances. We are witnessing today a crumbling of certain ideological systems. Look at Russia and China and Argentina. And the young intellectuals in France. Those young intellectuals, they are called, the new young philosophers in France today, have declared that collectivism has been a total failure. Everything has fallen. Leninism, Marxism, Stalinism, Maoism and even Capitalism. We have completely wiped everything clean. We are starting all over again. Man is re-beginning today. He’s going to begin again tomorrow to reconstitute his life and society by other means. These means have already been given to us in part. For example, Christian morality or Judaism which give us the elements of a morality which is very ancient. The religions give us some moral basis which is very old and yet are very avant-garde, very contemporary at the same time.

DB. In Rhinoceros, while resisting many rules of traditional or bourgeois drama, you have still created a work which is classical in form. Why is that?

EI. For several reasons. First of all, it is very important to me that the play be understood by the majority of the audience. In spite of its apparent formality of sticking to the classical form as you said, and despite the fact that it might seem to be classical in form, quite a few strange things happen in the play that have never been seen before. For instance, the transformation of people into rhinoceroses. Another reason is that writing a play is also an experience in style, writing style. So I used a style that is classical. Take for example Picasso, who after having been a cubist became a classicist for a while and then he came back to his style to neo-cubism. So it was not only an experience in writing style but also it was very important that people understand the play. As a result I wrote it in a form that I felt would be most comprehensible to the majority of the people and at the same time allow me to experiment with style and put my own feelings into it. Over and above the problems, the dramatic problems that confront an author when he is writing, there are other important things. It’s very necessary that the work of art be received. Otherwise the play would be nothing more than a discourse or a few words that he has spoken to somebody. What is typical of a work of art is that it’s not dressed. A group of ideas. It is the way in which they are expressed that is important. Is Rhinoceros a play or is it a discourse, a speech? The ideologists were greatly confused. They didn’t realize the artistic quality of the play and in doing so they made a great error in thinking. Say there is a marksman who fires on people, friends of his people. That the marksman fires on the friends of his people does not prove that he is not a good marksman. It has nothing to do with the quality of his ability. And if there is a bad marksman who fires on the enemy of his people, then one cannot say that he is a good marksman, just because he fires on the enemy. Over and above all, the anxieties and all the problems, what is most important is the realization of a structure. That is the artistic judgement. Our spirit, our mind, is expressed through our culture, through these artistic structures. The temples of antiquity are no longer temples, but they still express the beautiful laws of architecture in form and that man was able to identify himself through this art. For example, the theatre of Luigi Pirandello is no longer of value, or valid in terms of psychology. This is because the psychology of Pirandello is very rudimentary, very basic. All the new vogues in psychology and psychoanalysis have left him behind. But why can we still go to a play by Pirandello and enjoy it? It cannot be solely for his ideas because his ideas are no longer a la mode, they’re passe. But it’s for the vivacity, the vivaciousness of the passions, and just to enjoy the success of the structure of the work of art. This beautiful form. There are several ways to judge a theatrical experience. One can judge it from the point of view of psychology, from a sociological point of view, from the Marxist viewpoint, or from a humanistic point of view, et cetera. But despite all these ideas and all these doctrines, if it’s a work of art and it is well done, it will remain throughout the centuries. For this reason we can still appreciate Oedipus Rex, though the social laws of antiquity no longer interest us. But the play expresses other aspects. For example, the futility of our destiny. This is always a contemporary problem.

EI. For several reasons. First of all, it is very important to me that the play be understood by the majority of the audience. In spite of its apparent formality of sticking to the classical form as you said, and despite the fact that it might seem to be classical in form, quite a few strange things happen in the play that have never been seen before. For instance, the transformation of people into rhinoceroses. Another reason is that writing a play is also an experience in style, writing style. So I used a style that is classical. Take for example Picasso, who after having been a cubist became a classicist for a while and then he came back to his style to neo-cubism. So it was not only an experience in writing style but also it was very important that people understand the play. As a result I wrote it in a form that I felt would be most comprehensible to the majority of the people and at the same time allow me to experiment with style and put my own feelings into it. Over and above the problems, the dramatic problems that confront an author when he is writing, there are other important things. It’s very necessary that the work of art be received. Otherwise the play would be nothing more than a discourse or a few words that he has spoken to somebody. What is typical of a work of art is that it’s not dressed. A group of ideas. It is the way in which they are expressed that is important. Is Rhinoceros a play or is it a discourse, a speech? The ideologists were greatly confused. They didn’t realize the artistic quality of the play and in doing so they made a great error in thinking. Say there is a marksman who fires on people, friends of his people. That the marksman fires on the friends of his people does not prove that he is not a good marksman. It has nothing to do with the quality of his ability. And if there is a bad marksman who fires on the enemy of his people, then one cannot say that he is a good marksman, just because he fires on the enemy. Over and above all, the anxieties and all the problems, what is most important is the realization of a structure. That is the artistic judgement. Our spirit, our mind, is expressed through our culture, through these artistic structures. The temples of antiquity are no longer temples, but they still express the beautiful laws of architecture in form and that man was able to identify himself through this art. For example, the theatre of Luigi Pirandello is no longer of value, or valid in terms of psychology. This is because the psychology of Pirandello is very rudimentary, very basic. All the new vogues in psychology and psychoanalysis have left him behind. But why can we still go to a play by Pirandello and enjoy it? It cannot be solely for his ideas because his ideas are no longer a la mode, they’re passe. But it’s for the vivacity, the vivaciousness of the passions, and just to enjoy the success of the structure of the work of art. This beautiful form. There are several ways to judge a theatrical experience. One can judge it from the point of view of psychology, from a sociological point of view, from the Marxist viewpoint, or from a humanistic point of view, et cetera. But despite all these ideas and all these doctrines, if it’s a work of art and it is well done, it will remain throughout the centuries. For this reason we can still appreciate Oedipus Rex, though the social laws of antiquity no longer interest us. But the play expresses other aspects. For example, the futility of our destiny. This is always a contemporary problem.

DB. Rhinoceros has been played as tragedy and also as fantastic farce. Are both interpretations valid?

DB. Rhinoceros has been played as tragedy and also as fantastic farce. Are both interpretations valid?

EI. Yes. I see no great difference between tragedy and comedy. In comedy man is laughable and in tragedy he is also ridiculous. What is important in Rhinoceros is that people understand the message of the play, the resistance to slogans, whether they be commercial or political, and the right to free thought. Universal truth is carried within ourselves and it is society as a whole that prevents us from arriving at this universal truth. We have to find it within ourselves. We are obliged to come back to it. A certain French writer said that the universal is in the individual, and the particular is in collectivism, or that which is in fashion at the time. It’s absolutely essential to return to the depths of our minds, our own souls within ourselves. This is a very old idea which dates all the way back to Plato. He said that it is within ourselves that we must find certain archetypal truths.

DB. In your most recent film, La Vase, even more so than in your earlier works, you seem to be using pessimism as a catharsis. Either that, or it is pessimism pure and simple. How is this a departure from Rhinoceros?

EI. It is a question of a message quite different from the message in Rhinoceros. Rhinoceros is a psychological, sociological and morality play, not in the religious sense, but in the sense of it having a message, a moral message. The character in La Vase is on a completely different level, a metaphysical level. He has left life, he has resigned from life. He’s pulled away from creation because he thinks the universe is very badly constructed and he hopes that another creation can be successful. This is a little bit the point of view of the agnostic philosophers who thought that the world was not created by God but rather by a demon who discovered certain secrets of fabrication and construction and made a world that was completely unsuccessful. The character in La Vase is mad, angry with the creation, while Berenger in Rhinoceros is angry with man. He is against man but he is for man. There is the difference.