Christopher Isherwood

Interviewed by DJ Bartel

Christopher Isherwood (1904-1986) was the author of The Berlin Stories, a pair of autobiographical novellas, Mr. Norris Changes Train and Goodbye to Berlin, later adapted by John Van Druten into I Am a Camera, the National Critics Circle’s Best American Play of 1952, starring Julie Harris as Sally Bowles, and a film of the same name and the same Julie Harris, by Harry Cornelius, then transmogrified by Joe Masteroff into the Broadway musical Cabaret, and splashed onto the big screen by Bob Fosse as the film starring Liza Minnelli and Michael York. If you think you’ve know The Berlin Stories by having seen Cabaret, then you haven’t read The Berlin Stories. Isherwood revisited his time in Wiemar Republic Germany in his memoir Christopher and His Kind. He wrote nearly fifty books, including A Single Man, a novel about a middle-aged English professor in L.A. grieving the death of his partner; and Journey to a War, a travel book about the Sino-Japanese War in prose & verse which Isherwood wrote with W.H. Auden, with whom he came to the U.S. from England in 1939. Upon arriving in Los Angeles, Isherwood became a Hindu, and as such wrote extensively for Vedanta and the West, the official publication of the Vedanta Society of Southern California and served as managing editor and on the editorial advisory board, working with the writings of Aldous Huxley, Alan Watts, J. Krishnamurti, and many others.

The interview was conducted by DJ Bartel July 9, 1979, at Isherwood’s home in Santa Monica, in anticipation of the author’s seventy-fifth birthday, August 26.

First, there is that voice, unhurried but nervous nonetheless, answering the davenport door bell, “I’m coming,” as if to add, “don’t go.” A moment later Isherwood appears below on the walkway. He looks older, even from the back of his head, which is cropped closely, almost no hair on the sides. When the door opens I look upon the strained smile of a century. Too portentous, perhaps, but there he is: Isherwood of Bohemian London, Isherwood of libertine Wiemar Germany, of Swami Ramakrishna, of Auden, Britten & Huxley. The student who scribbled limericks on exams to get kicked out of Cambridge was also the sin-reveler who between drunken episodes translated the Bhagavad Gita. Now, with the rest of them gone, even his guru Prabvanvananda, Isherwood remains on the edge of a canyon, with a view of the Pacific, standing among a small and dwindling handful of acknowledged masters from before and after the Third Reich. His name is in the phone book. He’s amazingly busy for a man his age, and evidently has patience to sit for an interview with some kid journalist.

To hear part of this interview with Isherwood, click on arrow.

DJB In the 1930s, you and several others, notably W.H. Auden and Stephen Spender, engaged in various political activities which were considered leftist at the time, yet you say it was impossible for any of you to have joined the Communist Party because you were going through a “Poet’s Revolution.” Would you explain what that was?

CI The phrase sounds rather pretentious. I would never describe myself as a poet, in the first place. No, what it really means is we were too individualistic to fit into this kind of thing. It was all very well to go to Spain, but actually to take part in political activity is something that I’d never done until I got to California. That is to say, I now engage in very simple civic political activity from time to time. I vote, or I appear here or there, and I speak for the American Civil Liberties Union and also for their Gay chapter. That’s why I find myself actually far more political now than I was then. In those days it was all mostly enthusiasm which was not really channeled into any particular activity unless, as you say, Auden’s going to Spain was a political activity, and so was Stephen’s going to Spain. And I suppose by stretching it a very long way you might say that Auden’s and my going to China was also a political activity in that a war was going on and we did make what amounted to political speeches. But all this was very superficial. It was much more the kind of thing that any rather adventurous young people might have done for the sake of the adventure.

DJB You didn’t consider Berlin Stories to be subliminally political?

CI Oh, certainly. I was raised as an historian and I’ve always been concerned to give a sense of the goings on of any particular period that I am writing about. To give a kind of dialectical view of the whole proceedings, in a larger frame of reference. That applies just as much to a book I wrote fairly recently, Kathleen and Frank, which is about my mother and father. It is really a history of England from the 1890’s to about the end of the first war. It’s so full of social history. I did so much boning up in order to write it. I feel that it is almost more of an historical work than anything else.

DJB Mr. Norris began as a much larger book called The Lost, which never got written. Were Sally Bowles and Goodbye to Berlin attempts to complete that book?

CI Well, yes. You see I was very much under the spell of Balzac and writing enormous words that would sort of take in the whole of human life, and all these characters, all the people I’d known in Berlin, were all waiting as though I were a refugee officer in some place like Hong Kong where these people are crowding in. You had to find a place for them, and you look in despair because you cannot imagine how you’re going to fit them into the available housing, and this is exactly what I felt like when I was trying to write a novel about my Berlin life. My first real tremendous breakthrough was when I decided that I wouldn’t write a novel and attempt to have all the Berlin characters in it together. Now this sounds like an absolutely idiotically simple decision to come to, but it tortured me and finally I thought, well, what do I really know best? What do I know backwards, forwards, and sideways? And I said to myself, the life of this Mr. Gerald Hamilton [British critic known as “the wickedest man in Europe], who was called Mr. Norris. That I could really write about. All right, I said to myself, you’ll forget about everybody else, and write that. Then I was tortured by what to do with all the rest of the people. How can I arrange them? There ought to be a plot. So I made the most incredibly complicated plot, and I thought I’d get them into it, though of course they wouldn’t stay in the plot. Then as it were, another voice from heaven or Mt. Sinai or somewhere spoke and said, “Why have a plot?” These are the most dazzling insights – these obvious remarks – when the right person says it at the right time. I was writing another book at that time, about my experience with the Quakers, and I wanted to put in all the refugees that I’d known when I was working with the Quakers which was a cast of at least fifty people. Suddenly, one day, one of my friends said, “The refugees are a bore.” And this again was like some dazzling insight. All the refugees were thrown out. It turned out to be my worst novel anyway, The World in the Evening. But this is typical. You go into these jams, and then suddenly you see how to do it. Right now, I’ve got exactly the same situation ahead of me. I’ve got these enormous diaries that I started keeping as soon as I got to this country and I thought now you’d better keep your eyes and ears open. This book that I’ve just finished isn’t so bad because it keeps to its point which is my relations with this monk. [My Guru and His Disciple] But now I have an enormous mass of undigested material dealing with working in the movies and knowing an enormous number of people in show biz and also a considerable number of, as they say, intellectuals, like Bertrand Russell or Gerald Herd or Aldous Huxley and others who have partially appeared in things that I have written already; but now there is a really great deal of material that I can’t bear to part with and I can’t imagine what this book is going to be like. I think it’s going to be a total mess. I solved the problem of the book called Goodbye to Berlin by saying it isn’t a book. It’s a lot of bits. And we’ll just put the bits together and it’ll be just as good as a connected novel because it all takes place in the same area and the reader will make up the joins for himself, and I have indeed found that again and again. Readers have imagined they’ve read a coherent novel when in fact they’ve read lots of little fragments about these people. It all adds up because it’s got an enclosing historical geographic area which holds it together, which is Berlin.

DJB You said about Mr. Norris Changes Trains you made a fundamental mistake, which is you tried to tell a contrived story. After this novel, you seem to be more interested in what you call “portrait writing” rather than plot and situations. Would you explain the change from what happened after Mr. Norris and what you consider a portrait novel?

CI I don’t think it should be thought of exactly as a change so much as that I was gradually finding out what it was I wanted to do. After all, the development of many artists, big and small and in all categories really, is that history of finding out what some part of them knows already from the beginning, that is, what they want to do, and what is most suitable to their talents such as they are. And this question is just as real if it concerns a quite middle-of-the-road or middle-class, middle-talented writer or a great genius. For everybody, there is always a search before they hit the absolute essence of themselves and feel that they can express it.

DJB Did this lead to more autobiographical writing? You left William Bradshaw behind and brought in Christopher Isherwood after Mr. Norris.

CI Yes. Of course, at first, I was thinking in terms of fiction so to speak. It’s not that I don’t think in terms of fiction now. I rearrange things a bit from an artistic point of view, because when you’re telling a story you’re telling a story, I don’t care whether it’s a fish you’ve really caught in a bay or if it is a fish that you in fact didn’t catch but pretended you’ve caught. The same thing applies. You build up to a climax. T.E. Lawrence, Lawrence of Arabia, says somewhere in The Seven Pillars of Wisdom that his Arab tribesmen, his allies, were marvelous storytellers who would tell the stories about the battles they just fought in, but they turned them immediately into a great epic. It was an art form, in fact, to tell just what had been happening that very week.

DJB You said, “With me everything starts with autobiography.” I’d like to understand this better by asking for your response to this observation, that, especially in the later stories in which Christopher Isherwood appears as a character, they are not so much about Christopher Isherwood as they are a chronicle of the events he witnesses, and he witnesses them in a rather detached way. Christopher Isherwood may sometimes be engaged in the story, but mostly he’s observant.

CI I think it is very autobiographically true about me personally that in many situations I prefer to shut up and listen to somebody, watch somebody else, and enjoy it. This is a personal idiosyncrasy. I don’t always want to burst into the conversation and take a leading part of it, although I do quite a bit of that too. In fact, I’m often told that in my old age I interrupt people. But each story was a perfectly sound biographical account. I tended to sit in a corner and watch these people. It’s true that other times I sort of got into the action and took part, but it isn’t an entire falsification of my character or my life to say that I was watching these people some of the time and thoroughly enjoying it. To this day Don and I very often say to each other, “Oh yes, I’d very much like to meet her if one could just sit in a corner and watch her.” In other words, you don’t want to get into a big thing, you don’t want to get involved with this particular person. One is usually speaking of some very showy individualistic famous character. Your instinct would be much more, I’m sure, that you would just like to sit there and watch them speaking to other people, watch them making decisions, what them moving about in the course of their lives. This is what’s fascinating. This is not a sign that you are a modest violet or a retiring person but just that it’s another function of pleasure. I never mind waiting for people at the airport because I just adore watching all the people, all the travelers. Sometimes I feel as though I could never tire of it.

Hear Christopher Isherwood practicing politics.

DJB In Lines and Shadows, which you intended as an autobiography, there is one crucial omission. Whenever you refer to your mother you do so as “my female relative” or something to that effect. Why?

CI When you come down to it, I felt that I’d dealt with the familial aspects of my life. As a matter of fact, I hadn’t, because I went on to write Kathleen and Frank. We all get into difficulties of this kind because life is very untidy. For example, in the book that I’ve just finished I wanted to stick to a certain character whom the book is about and describe my relations with that character over a period of years; to be specific, from the year 1939 to the year 1976 when he died. Now all that time that I was meeting with this character and spending time with him and having a relationship with him, all the rest of my friends, and all the rest of my activities, divided themselves into two parts. One was the people who knew this character and therefore had a place in the story of our relationship, and one was the people and the activities that didn’t for one moment impinge on the life of this character, so they’re left out of the book. Now this produces peculiar features: there is only one mention in the entire book of Stravinsky, Garbo is mentioned only twice and so on. Even Aldous Huxley doesn’t appear nearly as much as he will in the next book because he was partly involved but not totally involved. Sometimes I was away from this person, having all manners of the most fascinating experiences, but they’re not mentioned because it’s not to my point. In the same way my mother and my brother were not to my purpose in writing Lines and Shadows.

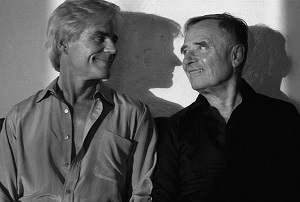

![[ E. Upward & C. Isherwood ]](https://djbartel.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/DJB-Upward-and-Isherwood-300x400.jpg)

DJB The writings that you did with Edward Upward at Cambridge, could you tell us about those?

CI I suppose they were what we’d loosely call surrealism. They were also highly pornographic. We did them entirely to amuse each other, and in fact we would aim to write them often late at night and produce them at breakfast. We were both students at the same college and we had rooms – as they say at Cambridge – on the same staircase. And so, we were almost living together. We saw each other constantly, and we talked about nothing except writing and literature. We wrote these things to amuse each other. I suppose they had a big basis in Edgar Allen Poe, a sort of macabre thing with the eroticism used really as kind of shock tactics. In other words, they weren’t sensuous, they were – I always hate the word pornographic – but they were shocking. They were meant to shock other people. For us they were a big joke, obviously. We laughed till tears ran down our cheeks. We also created a myth about Cambridge itself. This I went into in considerable detail, all except that I couldn’t put in the pornographic parts in those days, in Lines and Shadows. We had a whole myth about the college, the faculty. The whole idea that we were sort of spies and secret people living in a world which we totally despised. Therefore, in a way, any kind of contact that we had with the other students, the other undergraduates, was a form of treason to this life that we were living because we had to act like ordinary young men. We got around that by treating it like play acting. In fact, Upward, who was very athletic, even got on the college team and did all sorts of things like that and played poker endlessly because that was the thing to do. Even I played poker and had a motorcycle, but it was all playacting which referred back to our stories and what we called Mortmere, an imaginary village where all these weird, mythological people lived. So it was a way of reflecting these activities into the distorting mirror of Mortmere and making them seem absurd. And we had fun.

DJB Did you save the limericks you used for answers on the exams?

CI I have probably got some of them. They were really very, very unsatisfactory. I’m ashamed of them. Of course, everything had to be done on the spur of the moment. The great thing to do was to ensure the fact that I not only failed, but that I should be asked to leave the college. That was the object of the proceedings. And I went straight off into what in my mind was an earthly paradise. I became the secretary, I was only twenty-one, to a string quartet, and entered the whole world of London Bohemia. By a string quartet, I mean a classical string quartet that played Debussy, and Faure, and the C-sharp-minor Quartet of Beethoven. This type of material. The quartet was associated with two really famous musicians. Casals used to come and play with them occasionally, and also Cortot, the pianist. I saw this London world of studio parties; met and saw in the distance other famous artists, writers, all sorts of people, and just thought I was the luckiest boy alive, and got paid one pound a week.

DJB Stylistically, it appears you have a certain debt to Catherine Mansfield and also to E.M. Forester. Are there others?

CI Yes, I would say there’s a great debt, that is not apparent in the style so much, to D.H. Lawrence. What D.H. Lawrence said to me in effect was never mind what that canyon looks like, how does it look to you this morning when you’ve got a violent hangover and have just been left by your lover, when this has happened and that has happened. In other words, it’s his world sort of totally subjective approach to what he wrote about that makes his writing enormously exciting. Of course, I know that that’s only, in a sense, the negative side of the genius of Lawrence, who I think a very, very great genius. But it’s the excitement of the whole thing. It’s all through him. Nothing is outside him. So you really narrow your gaze down as though you were under water looking through some kind of goggles and you explore the world of Lawrence. Mansfield influenced me autobiographically. That is to say the tone of her diaries happened to be the first diary writer whom I encountered who turned me on. Her diaries and her letters. I loved just the tone of her voice. Of course, now I know so many other diarists and letter writers, for example, one of my favorites is Byron but I’d never read his letters at that time. I do find I can still remember how turned on I was by Mansfield.

![[ W. Somerset Maughan ]](https://djbartel.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/DJB-W-Somerset-Maugham-320x400.jpg)

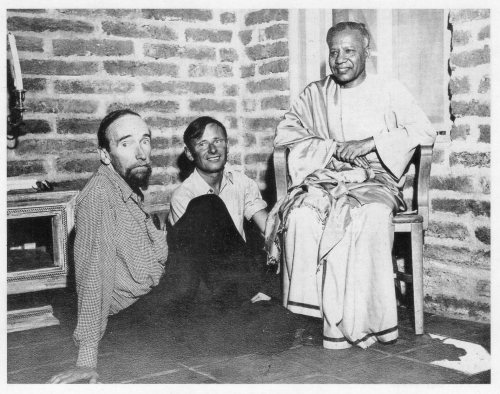

DJB Somebody mentioned Somerset Maugham.

CI Well, Maugham was a very good friend to me throughout my life. Curiously enough we were not really very intimately acquainted. But very shortly after he met me he started going around behind my back talking about me and saying what a good writer I was. An extraordinary act for Maugham – a man of his age and position. We always remained friends through to the time he died. I suppose I met him first in the thirties and went right on seeing him until the sixties. As for his influence, it exists in the marvelous organization, the economy of the tale telling, the exactness of the moves on the chessboard. He takes you from position A to position B and so on and moving to checkmate you in the end by utterly overwhelming you with the story. The good ones were unanswerable.

DJB After Auden and you left Europe the critical opinion was that the two of you were taking a large chunk of literature with you. Also, there was a good deal of concern that you might not be able to write in America. Whether or not that was a valid concern, the fact is it took you several years before another novel arrived, even though you were writing other things. There appears to be several reasons, or at least public reasons, for the absence of any fiction. Certainly, one of them was your increasing involvement with the teachings of Sri Ramakrishna. Did you find that as a fiction writer you were starting over again because of your move towards Vedanta?

CI Oh yes, in a way that certainly was a great big distraction from writing. Also, Swami Prabhavananda. They made a tremendous difference to me. And writing was complicated by the fact that I was also a pacifist, a conscientious objector, and therefore, something had to be done about that. What was done was that I got myself involved with the Quakers in a social project in the East. It was a hostel for refugees from Europe and I spent about a year there. That was another big distraction from writing. Also, Prabhavananda provided me with plenty of chores. They had a magazine I had to edit. Then I brought out a book of selected articles from the magazine. Then he wanted to translate the Gita, so we did that. All this was quite time consuming. Afterwards, after I’d written Prater Violet, I got into some more work for him. I did a translation of one of Shankara’s books and then another one of Patanjali’s Yoga Aphorisms with a commentary. So, he really provided me with plenty of work. After that, finally, I did a popular life of Ramakrishna and his disciples. But of course it was absolutely necessary, if I was going to live in this country, to become climatized before I could write anything meaningful. I wasn’t about to come here and make the kind of remarks of a total outsider in the manner of somebody just visiting a country. I didn’t realize when I came that it would become my home, in a far more profound sense than anywhere else in my life. We traveled around so much when I was young. I’ve never lived near as long anywhere else as I have in this house. I’ve lived more than half my life in the States, and of that life the great majority of the years were spent almost exclusively in the Los Angeles area and mostly in this very canyon in which I think I’ve lived in about twelve different buildings under different circumstances.

DJB After you had become climatized and become involved with the teachings of Ramakrishna, how was your fiction affected?

CI It’s very hard for me to answer that question, almost impossible because you see the aims of fiction are in a sense within the area that’s loosely called religious. If you write a novel about somebody, I don’t care how “evil” that character may be, the very fact that you’re writing about him presupposes a sort of pardon, a sort of mercy. You may disapprove intensely of his activities and yet you can’t help taking interest in him. You are forgiving him to a certain extent because you’re putting what he’s done to one side and saying nevertheless he fascinates me. I want to know him. So in that sense you might say that one didn’t need Vedanta or anything else, I mean any old novelist does that. If you can’t do that you’re just not fit to be a writer of that kind. You could be a polemical writer. You could write terrible renunciations of somebody, but a novelist per se, someone who engages to look into life and report on his findings, is not a naturalist. Or in another sense, he’s like a doctor. There’s no time for wondering what the moral condition of the patient is.

DJB Some of the books then might be considered pardons of Christopher Isherwood.

CI Well, yes, a temporary pardon. For instance, the doctor, continuing with this language, pardons a man as long as he’s sick. When he’s well again, the doctor says, “Now they’re waiting for you outside and they’re going to take you out and execute you.” Maybe the doctor approves of the execution, but he still works on his patient.

DJB Your translation of the Gita was by your admission an interpretation. It was not a literal translation. What kind of reception did it get from Hindu groups?

CI As a matter of fact, some of the greatest Sanskrit scholars in India were sent our translation. Prabhavananda said, “Admittedly you have to make allowances for the fact that this is written primarily as a literary work, but it always follows the text.” And they wrote back and said, “Yes, we have to admit that, that is quite accurate.” It’s just not accurate in the way a literal translation from the Sanskrit would be. Sanskrit is an intensely compressed and telegraphic kind of language, and there’s no way of absolutely conveying this unless you translate word for word and then give this sort of scrambled telegram to the reader and put in a paraphrase afterwards saying this, in effect, in English means so and so. Then you put in conjunctions and prepositions and everything else, and gradually start changing the thing. I took great liberties which are admitted to in the beginning. We wrote a perfectly straightforward translation of the thing and it was dull like you can’t imagine, and everybody got very discouraged about it. So I thought, well, let’s try some experiments. So I just switched into various types of verse. I started off very simply with a kind of heavily stressed alliterated stuff that sounds rather like early British epic poetry. “Krishna the Changeless, horse by chariot, there where the warriors bold for the battle face their foe-men between the armies. There let me see them, the men I must fight with, gather together.” This kind of thing. Then I thought we’d try some hexameters, so we did another part of it in hexameters. And then I did some sort of dubious things that were vaguely based on my memories of Latin poetry of one kind or another, the different forms used by Horace or Virgil or whatever. But the proof of the whole thing is that it has been a steady success among the various available translations of the Gita, and not just from a literary point of view. An awful lot of people were really turned on by it to a serious interest in Vedanta and the whole Hindu thing. So it was worthwhile. It accomplished its purpose. It was just a deliberate decision to do the one thing rather than the other, because some extremely accurate and good and valuable translations of the Gita exist. There’s a very good one by another Monk of our order, Swami Vivekananda. He’s dead now, but he was the head of one of the [Vedanta] centers in New York. There, with copious notes and everything, he tells you exactly what these verses mean.

DJB Have you ever found a conflict between Vedanta and homosexuality?

CI Oh my goodness. I won’t say there was a conflict. There wasn’t a true conflict. But a great deal of my new book is about this. I mean, there would be really no ball game if it weren’t for my whole personality bumping its individualistic H’s against this extraordinary individual and testing him over and over again. That was of course my very first concern. I wasn’t going to go near this man if he was going to tell me I was a sinner. My God, all I needed to do was go to the nearest Baptist to be told that, and I’m sorry to say also in many cases to the nearest Rabbi because they have been upholding their end of Leviticus with enthusiasm. However, this man provided a distinctly satisfactory answer to my various problems without saying I was pure as the driven snow. Nevertheless, he was extraordinarily broad minded. As a monk he thought of all sex, from the most legal heterosexual marriage to every other kind of sex, as a diversion from what to him was the one purpose of life, to seek God. Therefore, when you really came down to it, he would have liked every single person he met to become a monk or a nun on the spot, and he quite admitted that this was not practical. And he didn’t demand it. He had a large congregation, a household congregation, almost indistinguishable in appearance on Sunday morning from any kind of Christian congregation, except that the Hindus do not demand that ladies wear hats or any kind of head covering in church. But it was very respectable, as they say. It is still to this day, and not freaky at all. We rather kept our Hinduism to ourselves. Many people who came to the lectures simply heard a kind of generalized type of philosophy which was richly illustrated with Christian examples. Prabhavananda, among other things, wrote an entire analysis of the Sermon on the Mount from the point of view of a Hindu. He read a great deal about Jesus, in accordance with one of the basic Vedantic propositions that all religions contain the truth regardless of how they vary in actual form. He always had an icon of Jesus on a shrine along with the figure of the Buddha and the pictures of Ramakrishna and his main disciples and various other Hindu deities, such as Krishna. He saw no essential difference in any of this. It’s just that he had a much more permissive attitude to the don’ts and thou shalt nots of Christianity. But then so do many Christians. My goodness, if I hadn’t become a follower of his I think I would have ended up as a Quaker. I found their religion magnificent while extremely exhausting because the first thing the Quakers do is give you a job which lasts all day, forever. It’s a total commitment.

DJB There’s another conflict which might have come about as a result of Vedanta. One critic says, “Because Vedanta teaches the necessity for detachment from all worldly desires and preoccupations and the elimination of self, it presents a conflict for the novelist who must draw on those very desires.” I think this would be especially difficult for a novelist who is writing close to autobiography.

CI Yes, but you see the critic is not quite watching his language here, because as a matter of fact art implies detachment. Let’s take the crudest example. A graphic artist is drawing a nude. Now, according to his personal predilections, he probably in many cases finds the nude attractive. But he completely sublimates the attraction that he feels because he is getting on with the art work. So as long as he is involved with the art work, he is in fact doing exactly that. He is rising above the desires. He renounces them.

DJB Maybe the critic was talking about it being a deterrent to the accumulation of experience that you can then write about.

CI Well, I never could imagine that anybody could lack experience to write about. I think that is a sort of myth. But that’s neither here nor there. It’s very nice when you’re young to say, “Oh dear, I must get some more experience. If I don’t get experience I won’t have anything to write about.” All you really mean is you want to get more fun. You want to go around, “Oh, I must go to Iceland. I must go to Tierra del Fuego, I must do this or that. I must have a lot more affairs with everybody. Because otherwise I won’t know about life.” But of course the actual truth is that a mouse in a prison cell knows about life. What we fundamentally know about is consciousness. Where you see a very good example of that is in some oriental art where people take one single theme, like the bamboo, and paint it over and over and over again. Never shall I forget going to stay with Georgia O’Keefe. One evening we spent about an hour-and-half looking at these oriental bamboo paintings that she had, and no two were absolutely alike. When I got into the mood, which of course was highly induced by her, I really began to find them interesting. And then I understood how extraordinarily little material you need. The whole point is to get the perception opened wide enough, that’s all that matters.

DJB In your introduction to Vedanta for Modern Man, you say that you believe Vedanta is most likely to influence the West through the medium of scientific thought, and eventually it will be relatively widespread. Certainly, it has a solid and comfortable foundation since Emerson backed it in this country. Do you think that the proliferation in the U.S. of certain religious groups of Eastern origin are evidence of influence by Vedanta?

CI I think it was absolutely inevitable that the impingement of the West on the East would produce a counter-movement. Indeed, very early in the proceedings, the British, just a very few of them, were taking the trouble to find out about Hinduism and so on. There were some foreigners who went to China and took the trouble to study. They went to Japan. With the interchange in which we kept giving techniques of all kinds to the East, the East was giving forth its goods to us, in a bad sense, in a good sense. Maybe this interchange has almost stopped now. We’re going on in sort of free fall. I don’t know. But certainly, we’ve gone through that period, there’s no question. We’ve received an enormous amount of stimulation from the East. My goodness, I remember when I first came out here. I was very soon in the position of talking to college groups and meeting lots of students and people. How different things were. I can get up on a platform now and I’ll be asked about being gay. I’ll be asked about literature, and what I am writing, but it always ends up with religion. There are always people who want to know. I was on the radio on Stonewall Day. People could call in to the station and talk to me on the air, and in all cases the questions asked were fundamentally religious, and in all the cases I had to say, “This is too complicated, I’ve only got five minutes. Will you call me at home later?” And they did. You see it’s extraordinary. That’s something that’s really happened since I’ve lived in this country, this enormous interest in the religious experience. And I don’t mean by that that I’m always running up against creeds, particular rituals, or attitudes. On the contrary, I find that it’s often not even necessary to discuss any of that, but they really want to know. “Whatever it is you do, does it work for you at all? You’re an old man now, you’re going to die,” as they always say with charming frankness. And I say, “Well, I’ll tell you, I’m certainly quite shaken by the winds of life and couldn’t hold myself up as a rock, but it does mean something, and furthermore it’s the only thing that means something and that’s it as far as I’m concerned.” And the other thing I say is that I believe that one can arrive at the truth – by the truth I mean the truth for oneself. I’m a good Jungian, in all manner of ways. I would never say that I was particularly fated to meet a Hindu. I might have gotten involved with a Catholic priest. The only thing that was profoundly against my feeling was the idea of confessing, because that never was my style. But I can imagine that the individual is so much more important than the group he belongs to. I can imagine a way-out Catholic priest just as, in some respects, you might say that Prabhavananda was a way-out Hindu monk. You have to have somebody that has a great deal of understanding, and that you’ll find in every denomination. I had a good deal of experience when I first came out here, meeting all these kinds of people. I got to know lots and lots of Protestant denominations and Fundamentalists. One of the people who struck me most was a Seventh Day Adventist who, with all due respect, did seem to me to hold beliefs which were incredibly restricted, from my point of view. Nevertheless, this man was so evidently beyond all this, and into a realm of love for his fellow humans, that he was one of the most remarkable people I’ve met since I’ve been out here. I can’t even remember his name anymore. I just met him a couple of times. Such people you meet. You also meet people who have nothing to do with religion, and people who say that they are atheists. That has nothing to do with it either, because all this is just semantics. One of Ramakrishna’s chief disciples said that he wished there was a separate religion for every single person living on Earth today. He thought one should be very individualistic about this. This is a very interesting observation. You might say, following the idea of individualism, that my relationship with Prabhavananda as described in my book, My Guru and His Disciple, is my religion. That is to say, what I was left with as a result of this relationship is all that I have, because it is the only thing which is predicated entirely on my own observation. At least I know what he said to me. At least I know how he strikes me. And that is enough. It wasn’t for one moment that I thought he was the only person in creation who could have been like that. He was the only person I’d met who was like that, and therefore he was my religion, and very individual as such.

January 17, 2019, djbartel.com – The unedited audio interview, is headed for the Isherwood archives housed at the Huntington Library in Pasadena, California. An official at the Huntington writes, “Your interview with Christopher Isherwood is such a gem. I gave a copy to Don Bachardy and he was really moved. He commented that the interview really captured Chris’ personality so clearly and that the questions were so deep and brilliant.”