DJB comments on “James Dean: Too Fast to Live, Too Young to Die”

“I wrote this in 1990 for the 35th anniversary of James Dean’s death, an event which annually receives far more attention than James Dean’s birth. I was re-booting my writing career after four years at WJHU in Baltimore and trying to publish as much as possible in my first months back. I knew next-to-nothing about James Dean, except the anniversary of his death would likely garner some attention. For three weeks I steeped myself in Deanology. I watched his three movies for the first time, and then I watched them over and over. I read what I could find about Dean in the Pratt Library, which wasn’t much. I experienced the James Dean phenomenon for the first time, three decades after it first occurred, not as a star-struck teenager in love with movies, but as a skeptical thirty-seven-year-old who disdained Hollywood films as false and emotionally manipulative. I must have thought I would slay the myth of James Dean and dance on his beautiful corpse. I got pretty worked up over it, but something other than slaying happened, and the piece turned into a study in form, similar to a Bach fugue, or an American flag by Jasper Johns. Over the years, “James Dean: Too Fast to Live, Too Young to Die” has been published several times in several cities, but first in Pittsburgh, September 19, 1990.”

James Dean

Too Fast to Live, Too Young to Die

Dennis Bartel

It’s been nearly a lifetime since James Dean took his fatal ride, 9-30-55, yet he’s still – no, he’s more than ever – part of the American shorthand. “Ten years?” shouts the Rebel to Mr. Magoo. “I want it now. I want an answer now. I need one!”

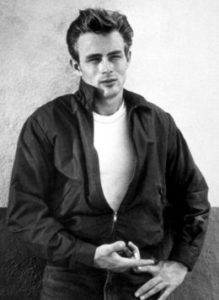

He lived and died in the early Elvis Era, but while Elvis was King, James Dean was us. “I don’t have to explain anything to anybody,” says James of Eden. Or is that Cal Trask? “Jesus Christ,” said Steinbeck, “he is Cal.” So it makes no difference, ‘cause in his famed and glorious cinematic trilogy, James Dean – who went from Fairmont, Indiana farm boy in work clothes, overalls, chino jacket, and camel-hair cap, to mumbling guerrilla artist, sullen enfant terrible, bongo-maniac – plays himself. Acting, the business of becoming somebody else, is in its dark heart a freakish thing, even (especially) when the great ones do it. I mean, what is that? Do you know beans about becoming somebody else? But James Dean wasn’t acting. No wonder we understood. He did what we all could do if we had the . . . the . . . “You sure have got a nerve, haven’t you?” says the bargirl at Kate’s.

Strasberg was his god, the Method his religion. Before going before the cameras, he would curl into a standing fetal position for several minutes, chin and knees together, holding his legs, and summon up a freight car of Midwest repression, “my inheritance incorruptible,” said Jimbo.

His mother died when he was nine. He used to cry on her grave, “Why did you leave me? Why did you leave me?” Over time, it changed into “I’m gonna show you! I’m gonna show you!” When James Dean told that story he would usually add, “I’m gonna be great!”

His mother died when he was nine. He used to cry on her grave, “Why did you leave me? Why did you leave me?” Over time, it changed into “I’m gonna show you! I’m gonna show you!” When James Dean told that story he would usually add, “I’m gonna be great!”

Everything seems to catch him off guard. It’s as new to him as it is to us. When he first kisses Natalie Wood she says, “Why’d you do that?” “I felt like it,” says the Rebel. When shooting was done on Rebel Without a Cause – before Pluto’s blood was dry on the planetarium steps, before Natalie was a virgin no more – James Dean came away shaking his head: “I could never take so much out of myself again.”

Everything seems to catch him off guard. It’s as new to him as it is to us. When he first kisses Natalie Wood she says, “Why’d you do that?” “I felt like it,” says the Rebel. When shooting was done on Rebel Without a Cause – before Pluto’s blood was dry on the planetarium steps, before Natalie was a virgin no more – James Dean came away shaking his head: “I could never take so much out of myself again.”

Speaking of Elvis, James Dean was Elvis’ silver screen idol. Elvis memorized all the lines in Rebel. “You can’t just go around pretending that you’re tough, even if you look a certain way, or… YOU’RE NOT LISTENING TO ME!” When Elvis came to Hollywood to start making his dopey movies, he would hang out at the old haunts where James Dean used to go. He got all shook up over a projected movie called The James Dean Story. “I wanna play that more than anything else,” said the King. We were spared this profanity when the movie was changed to a documentary. James Dean had a little something for Elvis, too. His favorite song was “You Ain’t Nothin’ but a Hound Dog.” He’d call up friends in the middle of the night and hold the phone up to the record player. He did it to Brando once. Brando was pissed.

Ah, Brando, we knew we’d get to the great actor, all hail. See, in the ‘50s the green-eyed pundits used to say James Dean was just a new brand of Brando. Even Jimbo himself paid tribute to the great actor’s deadly boo: “In this hand I’m holding Marlon Brando saying, ‘Fuck you!’ and in the other, I’m holding Montgomery Clift saying, ‘Please forgive me.’” Or isn’t this just James Dean stroking the tradition he would one day rule? Remember who’s holding whom? Elia Kazan, who directed both Brando and Dean in their breakthrough films (Streetcar, Eden), said where Brando was troubled, James Dean was “sick – a cripple inside.”

Decades later, Brando was still hangin’ round, the mega-star getting a billion dollars for ten minutes of work and looking not so much troubled as embarrassing. James Dean had the instinctual genius to gun his silver Porsche Spyder up California Highway 466 on that dusk of 9-30-55, thereby assuring, true to his word, his would be “a beautiful corpse.”

The corpse had a lopsided face. This is no lame stab at black humor (Jimbo’s favorite kind). James Dean actually believed he had a lopsided faced. He accentuated this with exasperated poses, said a friend, “as if one side of his face was slipping down or collapsing.” Kazan added, “His body was almost writhing in pain sometimes. He was very twisted, almost a spastic. He couldn’t do anything straight. He even walked like a crab, as if he were cringing all the time.” For the East of Eden Ferris wheel scene, Dean kept himself from urinating all day so he’d look to be in pain sitting high in the night sky with Julie Harris.

The corpse had a lopsided face. This is no lame stab at black humor (Jimbo’s favorite kind). James Dean actually believed he had a lopsided faced. He accentuated this with exasperated poses, said a friend, “as if one side of his face was slipping down or collapsing.” Kazan added, “His body was almost writhing in pain sometimes. He was very twisted, almost a spastic. He couldn’t do anything straight. He even walked like a crab, as if he were cringing all the time.” For the East of Eden Ferris wheel scene, Dean kept himself from urinating all day so he’d look to be in pain sitting high in the night sky with Julie Harris.

James Dean’s nearsightedness is the stuff of legend. He couldn’t see what was going on right in front of him, observed another friend, “so he fell back on himself, created a universe out of his body, his face and his words that forced the other actors to adjust to his rhythm – enter his world.”

But, you see, like I said, uh, I’m not really saying this right ‘cause, look, James Dean’s not about quirks and techniques, he’s about being confused and misunderstood and, oh I don’t know, you’re tearing me a-part!

I mean, to get right down to the serious jelly, James Dean did not fight the good fight, he fought the mean fight. “I’ve been jealous all my life,” Cal says, as he lays to waste brother Aron’s righteous illusions, then steals his sweetheart. “I don’t wanna make friends,” says the Rebel who’s not too chicken to pick up a switchblade. Jett Rink fender-bends a man’s car, then apologizes by re-arranging the man’s face. There are stories James Dean was a bad drinker. Two glasses of wine left him hammered. “When he was drunk his personality completely changed,” said a friend, “he was completely uncontrollable and could get vicious.” There were rumors of fights with girlfriends. (In East of Eden he’s drunk once, in Rebel Without a Cause he’s drunk twice, in Giant he’s drunk damn near all the time.)

Don’t get the idea the soul and substance of James Dean is nothing more than a drinking problem. It wasn’t just booze which made him grind his back molars. When Raymond Massey, O clerical father, demands to know why in Heaven’s name did Cal heave the ice blocks from the ice house, the very sober, very sulky farm boy mumbles, “Cause I wanted to see ‘em go down the chute.” When home-weenie Jim Backus won’t stand up for him to his mother, the Rebel, deranged with frustration but sober as a bullfighter, grabs his father by the shoulders and nails him to the floor. By the time Giant sweeps onto the screen, Jett Rink, his stomach lining eaten away by vengeance, has banished his parents to the dusty far horizon of memory, but Rink is still fighting with anyone for any good (or, no good) reason. James Dean is part of the shorthand: “Do you think I’m bad?”

All this rage makes me crazy. Somebody get me a bottle of milk.

Yeah, sure he’s bad, what of it? A reporter wrote: “He collected a small crew of sycophants, and if he thought he was not getting enough attention in a restaurant, he would beat a tom-tom solo on the tabletop, play his spoon against a water glass with a boogie beat, pour a bowl of sugar into his pocket, or set fire to a paper napkin.” When shooting was done on East of Eden, Julie Harris went to see him in his trailer and found him weeping uncontrollably. “It’s all over,” cried James Dean. “It’s all over.” “He was just like a child,” said Harris. Bad, self-centered, infantile, yeah, all of that, but he’s us. And when he’s not bad, when he’s probing life’s soft crevices, when his hyper-sensitive tenderness flinches on the surface, he’s still us.

When Cal seduces the bar girl to show him where Kate’s – er – Mother’s office is, he is clumsy and tongue-tied. Like us, he lacks the moves, he possesses hardly enough words to choke on. All he has are his moist, pleading eyes saying I gotta know who I am.

“He scares me,” says Julie Harris, and we in lewd rush reply, You’d better be scared, Abra sweetheart, cause sex with James Dean is going to be like sitting on a wire spring coiled tight enough to launch you clear to Monterey.

The Rebel – for all his red jacket, juvey hall insolence, for all his “Wanna explore?” come-on to Natalie – can’t function any better than we can in the face of love. When Natalie whispers her bard-like soliloquy of love, concluding, “I love you, Jim. I really mean it,” the Rebel can’t speak. He mumbles, “Um, um.”

Even James Dean’s failures in love are ours. Living out on his Little Reata dust heap, the dirt-poor Jett Rink fantasizes over tacked up newspaper clippings of the married Liz Taylor. By the time he hauls his tumbledown truck to Liz and Rock Hudson’s porch, and stumbles forward drenched in his very own high-priced Texas tea, Jett has tried to hit on Liz in every homegrown way he knows, and while Liz may have looked upon him as Mary Magdalene looked upon the cross, nothing has worked. Nor later does Jett’s Daddy Greenbacks act work on Liz’s daughter, Carroll Baker.

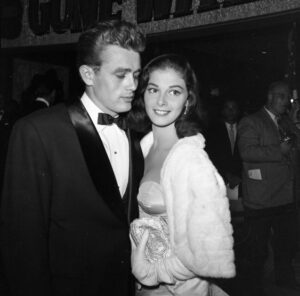

And look: a case of Life Is Bigger Than Hollywood. James Dean’s true love was an Italian actress named Pier Angeli. Among the many gifts of affection he and his “Miss Pizza” shared was a pearl ring she wore on the second toe of her left foot. But Pier’s mother disapproved of James Dean’s T-shirts and Levis, of his smart mouth and fast cars, of his non-religion and grim fascination with his own early death. Suddenly, Pier jilted James Dean to marry Vic Damone (imagine). The day of the wedding, James Dean waited on his motorcycle outside the church, and when the doors flew open and the happy newlyweds emerged, he gunned his bike for all to hear and roared off. But he was to have her yet. Eleven years later, Pier, after two marriages and a bitter child custody scandal, confessed to the world, “James Dean is the only man I ever loved deeply as a woman should love a man. I had to separate from my husbands because I don’t think one can be in love with one man – even if he is dead – and live with another.”

And look: a case of Life Is Bigger Than Hollywood. James Dean’s true love was an Italian actress named Pier Angeli. Among the many gifts of affection he and his “Miss Pizza” shared was a pearl ring she wore on the second toe of her left foot. But Pier’s mother disapproved of James Dean’s T-shirts and Levis, of his smart mouth and fast cars, of his non-religion and grim fascination with his own early death. Suddenly, Pier jilted James Dean to marry Vic Damone (imagine). The day of the wedding, James Dean waited on his motorcycle outside the church, and when the doors flew open and the happy newlyweds emerged, he gunned his bike for all to hear and roared off. But he was to have her yet. Eleven years later, Pier, after two marriages and a bitter child custody scandal, confessed to the world, “James Dean is the only man I ever loved deeply as a woman should love a man. I had to separate from my husbands because I don’t think one can be in love with one man – even if he is dead – and live with another.”

Come 9-30-55, James Dean left behind a great many women . . .

Suddenly violence shatters our reverie. It’s one minute to six. The sun is sinking fast. In the brown-weeded desert distance is the unmuffled growl of a four-cam sports car coming this way, eighty, eighty-five. Now the silver Porsche Spyder squirts over a knoll and into sight. It carries two men. Its wheels skim the dirt shoulder, spitting gravel. It roars past. On the tail of the car is painted “Little Bastard.” We will learn the Little Bastard bought this fly-weight racing Porsche for $7,000 only a week ago. We will learn only two hours ago the Little Bastard got ticketed for doing sixty-five in a fifty-five. We will learn the Little Bastard is on his way to Salinas (Steinbeck country) to enter a car race – something his studio has prohibited him from doing during the shooting of his last two movies. We will learn the Little Bastard is only twenty-four and on the brooding strength of one movie, one East of Eden, he has become Hollywood’s, well, Little Bastard. Just ahead is the town of Cholame. Just ahead is the junction of California Highways 466 and 41. Just ahead is a two-tone 1950 Ford Tudor, slowing to turn left. “He’s gotta see me,” says the Little Bastard over the shuddering howl of the 547 engine, “he’s gotta see me.” But he don’t see you, Jimmy, and this ain’t no chickie run.