Knabe Pianos

for Genteel People of Means

DJ Bartel

Lifetimes ago, Knabe pianos were among the finest in the land, manufactured in Baltimore by a venerable firm and played in home parlors, churches and school rooms, in the White House, and on the concert platform from Tennessee to Tokyo. Today, pianos – grand pianos, square pianos, and uprights – displaying the name “Wm. Knabe & Co.” have nearly vanished from the cultural landscape, and an important American contribution to music has disappeared with them.

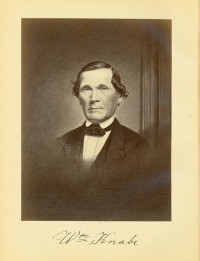

The story of Wm. Knabe & Co. (pronounced Kah-NOB-aye) is a 19th century tale of earnestness and pluck, salted with intelligence, taste and vision. It begins in 1803, in Germany, with the birth of Wilhelm Knabe in Kreuzberg, a small town near Berlin. Martin Friedrich Knabe, the town apothecary, and his wife Ernestine intended their son Wilhelm for a learned profession. But in 1812, Napoleon’s army marched through Germany, bringing the calamities of war. Like many families, the Knabes’ resources were devastated. Instead of attending the university, young Wilhelm, who showed an aptitude for mechanical things, was apprenticed to a cabinet and pianoforte maker.

The story of Wm. Knabe & Co. (pronounced Kah-NOB-aye) is a 19th century tale of earnestness and pluck, salted with intelligence, taste and vision. It begins in 1803, in Germany, with the birth of Wilhelm Knabe in Kreuzberg, a small town near Berlin. Martin Friedrich Knabe, the town apothecary, and his wife Ernestine intended their son Wilhelm for a learned profession. But in 1812, Napoleon’s army marched through Germany, bringing the calamities of war. Like many families, the Knabes’ resources were devastated. Instead of attending the university, young Wilhelm, who showed an aptitude for mechanical things, was apprenticed to a cabinet and pianoforte maker.

Following German custom, Wilhelm traveled six years learning his craft, and then apprenticed himself for three more years.

At 28, Wilhelm, known among friends for his uncommon order and keen perceptiveness, became engaged to the daughter of a physician, Christiana Ritz. But before Wilhelm and Christiana could be married, Dr. Ritz and his family decided to leave for America with a company of immigrants. Christiana’s brother had already helped establish a new German settlement in Hermann, Missouri. Wilhelm purchased a set of farm tools, and prepared to go with his beloved.

The family paused in the port of Baltimore to recuperate from a tragic journey. Dr. Ritz had taken ill and died aboard ship. Wilhelm and Christiana were married, and planned to remain in Baltimore a year to learn the new language and customs before continuing on to Missouri.

Wilhelm (now calling himself William) took a job with the German piano maker Henry Hartge, who had recently made a name for himself by creating iron frames for his pianos. After a year, William and Christiana sold their farm tools and settled in Baltimore. William must have managed his modest eight dollars a week with admirable economy. Within three years he started his own business in an old frame building – buying, selling, and repairing pianos.

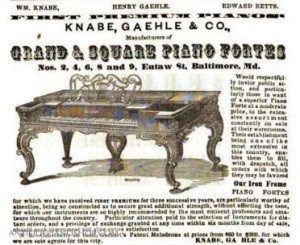

In 1837, William joined fellow German Henry Gaehle to form the piano manufacturing firm of Knabe & Gaehle. In keeping with the elite place the piano then held in American society, Knabe & Gaehle’s ads promised, “Pianos of quality for genteel people of means.”

At the time, European pianos dominated the American market, but besides Knabe & Gaehle dozens of firms were emerging along the east coast, notably two: Chickering and Steinway. Pianos became more affordable, thanks primarily to the newly developed American square piano. Also, the piano was becoming less strictly an article of luxury and more a necessity for home and hearth. One typical advertisement for pianos now implored: “Hold the family together.”

At the time, European pianos dominated the American market, but besides Knabe & Gaehle dozens of firms were emerging along the east coast, notably two: Chickering and Steinway. Pianos became more affordable, thanks primarily to the newly developed American square piano. Also, the piano was becoming less strictly an article of luxury and more a necessity for home and hearth. One typical advertisement for pianos now implored: “Hold the family together.”

Knabe & Gaehle, with business practices that were, as one historian remarked, “cautious, shrewd and scrupulous,” enjoyed seventeen prosperous years. Their small manufactory stayed busy producing five pianos a week. The firm’s principal market was the South, from Richmond plantations to Charleston townhouses.

As the most affordable piano, at about $200, the upright, gained popularity. (A Knabe grand could run $500.) Gaehle believed the firm could enhance its position by discontinuing squares and grands and concentrating its efforts on uprights. Knabe, whose kindly disposition appears to have rarely failed him, argued that they should continue to make all three classes of piano, not only offering superior squares and uprights, but competing with Steinway and Chickering to make the finest grands in America. The difference of opinion was enough to dissolve the partnership, which Gaehle did in 1854, and then forming his own firm. So William, likewise, set out on his own, founding the firm Wm. Knabe & Co.

Perhaps the break was uglier than it appeared. Within weeks, one of Knabe’s two manufactories was destroyed by fire. Five weeks later, the other manufactory burned. Then, with the important Maryland Institute Exhibition approaching, William’s stock of pianos was tied up in legal knots over the protracted end of the partnership. Already the fledgling Wm. Knabe & Co. found itself on the brink of ruin.

William responded with characteristic resolve. Swiftly, he and his workmen converted an old paper mill into an impromptu manufactory. They built one new piano in time to present it at the Exhibition, where it won the competition over twenty others.

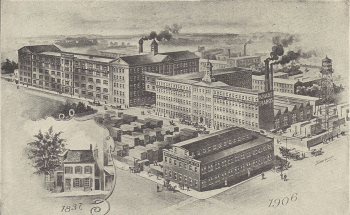

By mid-century, piano-making had outstripped its cottage craft stage. Huge work forces were required to meet the demand. In 1860, Wm. Knabe & Co. began building an immense new manufactory at Eutaw and West Streets, occupying over two blocks and employing 300 workmen, making it one of Baltimore’s largest industries.

Unlike other industries, Wm. Knabe & Co. turned out a product that required not only hard and painstaking labor but the finest artistry. A simple upright took six months to finish, and a grand up to two years. Knabe pianos were described by the New York Daily Tribune as having “a pure, full and equal tone, in quality melodious, rich and sonorous, housed in cases rich and elegant in design.” Knabes further enhanced their reputation at state fairs, where these “noble instruments of sterling merit” regularly carried away the Gold Medal. The rising southern antipathy toward all things northern added to this boon for Knabe pianos, which had long ago built a base of commercial support in the South. Wm. Knabe & Co. was now producing thirty pianos a week, and Knabe was becoming a household name below the Mason-Dixon Line.

The Civil War proved calamitous to industries in Baltimore, with the loss of the Southern trade, and nearly fatal for Wm. Knabe & Co. William appears to have born his reverses with equanimity, but the strain of impending ruin proved too much for his health. On his deathbed, in 1864, he instructed his two sons to save the firm by seeking new markets in the West.

Ernest Knabe, 37, and William Jr., 23, had each a received liberal education in schools and a practical education in their father’s shop. William Jr., quiet and retiring by nature, became manager of the manufactory and warerooms. The gregarious, music-loving Ernest became head of the firm. Bargaining hard with the bank, he secured a large loan to stabilize the business, then began touring. The pianos sold themselves, but surely Ernest’s warm-hearted burliness made for a good introduction.

The firm rebounded with vigor. Knabe pianos became well known in Pittsburgh, Chicago and San Francisco. America’s philosopher of self-reliance Ralph Waldo Emerson observed, “’Tis wonderful how soon a piano gets into a log-hut on the frontier.” A large percentage of those pianos were Knabe uprights. The firm also began exporting to Canada, and Knabes sold well in South America. Back home, in 1869, final additions were made to the manufactory at Eutaw and West. It was crowned by a cupola offering an extended view of Baltimore in all directions. Wm. Knabe & Co. was now producing forty pianos a week, 2,000 annually, and was again a formidable competitor in the flourishing American piano market. By 1871, Knabes had won 65 Gold Medals.

Aware that the more Americans loved music the more pianos they would buy, piano makers commonly financed concert tours and sponsored local concerts. Larger firms like Knabe also maintained circulating libraries of sheet music. Indeed, at the Centennial Exposition of 1876 it was declared that “music making would easily be cut in half” were it not for piano makers like Baldwin, Chickering, Decker Bros., and Gibbons & Stone. But heading the list were the companies of William Steinway and his princely friend and competitor, Ernest Knabe.

These two giants received the most testimonials from artists, and served as barometers of quality for artists and piano makers. Wm. Knabe & Co. could claim the great French composer Camille Saint-Saens played a Knabe. The company financed an American tour by the eminent German conductor Hans von Bulow, who played a Knabe at all of his recitals thereafter. Francis Scott Key owned a Knabe, as did Brigham Young (actually, he had three Knabes at his home in Salt Lake City). And the wildly famous American virtuoso Louis Gottschalk gave this testimonial: “The Knabe pianos, on which I have played, are exceedingly remarkable for their qualities of tone. The bass is powerful, without harshness, and the upper notes sweet, clear and harmoniously mellow.”

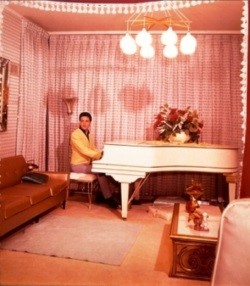

Under President Rutherford B. Hayes, whose wife Lucy instituted the tradition of White House musicales, a Knabe rosewood concert grand was installed in the President’s official residence. In 1879, the Japanese government made its first purchase of musical instruments – uprights for the country’s classrooms – and chose Knabe pianos, which were decorative but not too ornate, and backed by a five-year warranty.

Ten years later, William Jr. died at age 47. Despite this loss, Wm. Knabe & Co. soon reached its historical high water mark. In 1891, Ernest Knabe proposed to add an extravagant touch to the opening ceremonies of the nation’s most auspicious new musical showcase, Carnegie Hall. The Knabe firm, he announced, would finance the appearance of Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky, widely considered the world’s greatest living composer.

The white-haired Russian master was initially unaware that his trip had been financed specifically by Knabe. Upon arriving in New York he was surprised to learn that after his four Carnegie Hall concerts he was expected to conduct another concert in, of all places, Baltimore. Tchaikovsky was exhausted from two weeks of work and sightseeing by the time he boarded a Pullman for the all-night trip to Baltimore. He lay sprawled across the bed in his cabin, fully clothed. “I had no strength to undress,” he told his diary.

At dawn, the train pulled into Calvert Station and Tchaikovsky was taken to the St. James Hotel at Charles and Center Streets, where, despite the hotel’s advertised “European Plan,” he was received, as he said, “with cold neglect.” He slept, breakfasted, and walked through a drizzle to Albaugh’s Lyceum Theater for rehearsal. To his dismay, he found the orchestra – the touring Boston Festival Orchestra led by Victor Herbert – under-manned, fatigued and under-rehearsed. “Only four first violins,” Tchaikovsky complained, “and the orchestra did not know my Third Suite. Mr. Herbert had not even played it through, although it had been promised that this should be done.” In place of the Third Suite, Tchaikovsky substituted the easier Serenade for Strings. His First Piano Concerto was also rehearsed (on a Knabe grand, of course), with the young pianist Adele Aus der Ohe, a former pupil of Liszt, who had successfully performed the work with Tchaikovsky in New York. “The orchestra was impatient,” Tchaikovsky lamented. “The young leader [concertmaster] behaved in a rather tactless way, and made it too clearly evident that he thought it time to stop.”

Tchaikovsky had just enough time to return in the rain to the hotel and dress in his performance frock coat. The two o’clock matinee was far from sold out. The Baltimore Sun reported, “None but musical people were present.” Ticket prices ranged from $1 to $1.50. In addition to Tchaikovsky’s works, the overture to Weber’s opera Der Freischutz, and a few miniatures by Victor Herbert were played, led by Herbert. For one critic, these latter occasioned the only sour notes of the concert. He called them “a bunch of scrappy selections.” Otherwise, as local newspapers described, “The Greatest Composer Living” and his music were received by the audience with applause that broke into cheers. Tchaikovsky, relatively new to conducting and still somewhat awkward on stage, acknowledged the ovations by making curt bows. Following the Piano Concerto, he was recalled five times, and each time tried to hide behind Aus der Ohe (whose name had been accidentally omitted from the program). In a letter home, Tchaikovsky later offered grudging praise for the orchestra which despite the poor rehearsal he thought played “quite well. [But] I didn’t sense any special delight in the audience, at least in comparison with New York.”

After the concert, Tchaikovsky had no sooner changed clothes back at the hotel when he was visited by “a Mr. Knabe,” whom he described as a man of colossal girth and hospitality. Ernest shepherded the great composer to a feast at his own home, where a choice company of two dozen Baltimoreans were in attendance, including the Director of the Peabody Conservatory and the Sun music critic. The food that night, according to Tchaikovsky, would be the finest served him in America. “Terribly delicious,” he noted. Ernest zealously kept the wine coming. The meal was followed by conversation, tricks, music, and smoking and drinking. A young local composer named Richard Burmeister foisted his own music upon Tchaikovsky by taking a place at a Knabe square piano and playing his own piano concerto. Tchaikovsky politely did not comment. The evening carried on long after Tchaikovsky had tired of enjoying himself. “A terrible hatred of everything seemed to come over me.” After midnight, l’affaire finally ground to an end and Knabe escorted Tchaikovsky back to the St. James. “I slumped down on my bed like a sheaf of wheat and at once fell dead asleep,” Tchaikovsky recorded.

Next morning, Knabe arrived uninvited at Tchaikovsky’s room to take him to see the city’s sights. Tchaikovsky was feeling “the peculiar American morning fatigue” that had plagued him since arriving in this country, and wanted nothing to do with the exuberant Knabe. But when he learned that they were being joined by Aus der Ohe and her sister (a lawyer named Mr. Sutro also came along), Tchaikovsky acquiesced.

It was rainy. The first stop, naturally, was the Wm. Knabe & Co. Piano Manufactory, which had grown to become third largest in the world. The main building rose five stories above Eutaw Street and was connected by a bridge over West Street to a second structure four stories high. “We inspected the whole enormous piano plant in every detail,” said Tchaikovsky. Transportation between floors was by steam elevators. The boiler building housed what one journalist called “one of the most beautiful and perfect engines in the country, of about 35 horsepower.” It had recently won the Gold Medal at the Maryland Institute Exhibition. A labyrinthine system of steam-pipes distributed heat to the large rooms filled with heavy machinery, and to varnishing rooms, finishing rooms and drying rooms where 200,000 feet of lumber dehydrated at a constant 140 degrees. The adjoining yards contained one million feet of lumber, undergoing nine years of seasoning in all types of weather.

Tchaikovsky was impressed by the large planing machines and jointing machines, the circular saws, the lathes and drills. But above all he admired the industrious spirit of the manufactory. “The sight of so many workers with serious, intelligent faces, so clean and carefully dressed despite the manual labor, leaves a fine impression.”

Lunch and champagne followed the downtown tour, then Tchaikovsky bid Ernest Knabe goodbye and boarded the train for Washington. Ernest promptly shipped a Knabe square piano to Tchaikovsky’s country house at Klin, Russia.

Ernest lived only another three years. Wm. Knabe & Co. had always been a family business, employing many members of the extended family, but with the death of Ernest it went public. In 1908, it was absorbed, along with Chickering, by the American Piano Co. of East Rochester, New York. The great manufactory was sold to Sweetheart Paper Cups. A few Knabes continued to be made, but those were in name only.

Knabe’s principles of “Tone, Touch, Workmanship and Durability” had helped to lift American piano making to the highest echelon in the world. Now the name Knabe, which had once evoked both populism and sophistication, began to be erased from the American musical page. But not before some last flickers of glory. In the 1930s an old Knabe grand became “The Official Piano of The Metropolitan Opera.” Knabe went out with apt style, accompanying America’s favorite opera stars, the likes of Kirsten Flagstad and Lauritz Melchoir. And no less a figure than Albert Einstein, who is said to have loved music with the same intensity as he loved science, played music at home on his own Knabe piano.