DJB comments on the following work.

“Kurt Vonnegut was coming to Pittsburgh to give a speech and promote a new book. While having long since left the Steel City, I still had friends and contacts there, so I contracted with a contact to interview one of my favorite writers from college days. It was late February 1992. A cease fire had been reached in Somalia, and Ross Perot had just announced on The Larry King Show he would run for U.S. President. In four months, Senator Al Gore would publish his cautionary book Earth in the Balance: Ecology and the Human Spirit, and the UN’s Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro would convene to discuss sustainability.”

Kurt Vonnegut and so on

An Interview by Dennis Bartel

Listen.

It was many years ago. Here was another kid taking the free ride through public school, and upon graduating he did not know much how to read. To his amazement, and entirely because of skills not honed in the classroom, he found himself in college. Suddenly, everyone around him, even the dullest, had long since advanced their reading beyond Sports Illustrated. Was he surprised to discover his college professors expected him to put his eyes on the page and leave them there a long time? Desperate and groping for something to save him, to teach him the rudiments of concentration, understanding, all stuff he had not learned, he happened upon an odd-size paperback with a bright red and yellow cover which caught his eye. It was Breakfast of Champions and it made perfect sense to him. He liked the funny drawings, too. He thought, If this is what reading a book is, I’ll read another. Which he did. It was Slaughterhouse-Five.

And so on.

He went on to make a habit of reading books. Over the years, he read several written by Kurt Vonnegut.

The Old Master himself tells a story about reading. He says he started reading in earnest when he was eight. He found simply by reading he could internalize the written words of people who had seen and felt things new to him. “The world dropped away when I did it,” he writes. Today, he calls reading “Occidental-style meditation,” in reference to a brief fling he had long ago, at the behest of his first wife Jane, with Transcendental Meditation. “When I read an absorbing book, my pulse and respiration rates slow down perceptibly, just as though I were doing TM.” The difference was, he says, when he awoke from his Occidental-style meditation he was “often a wiser human being.”

The Old Master himself tells a story about reading. He says he started reading in earnest when he was eight. He found simply by reading he could internalize the written words of people who had seen and felt things new to him. “The world dropped away when I did it,” he writes. Today, he calls reading “Occidental-style meditation,” in reference to a brief fling he had long ago, at the behest of his first wife Jane, with Transcendental Meditation. “When I read an absorbing book, my pulse and respiration rates slow down perceptibly, just as though I were doing TM.” The difference was, he says, when he awoke from his Occidental-style meditation he was “often a wiser human being.”

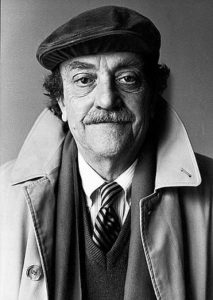

A product of the Great Midwest in the Great Depression, now living in Sagaponack on the far, cold tip of Long Island (where this time of year he cannot take his usual afternoon walk, so he watches TV), Kurt Vonnegut remains atheist and wry of eye. More so. His laugh is cigarette-tar-choked and unrestrained. Several books ago he dropped “Jr.” from his name, after his father died. His newest book (opus 18, but you get the feeling he’s not counting) is Fates Worse Than Death (An Autobiographical Collage of the 1980s), a memoir consisting of occasional writings such as magazine essays, introductions to other writers’ books, speeches, sermons and more all teeming with mushrooming parentheses, and deftly stitched together in a conversation Vonnegut casually conducts with us, like he did in his memoir Palm Sunday (1981).

Of course, it is not us he’s conversing with. We’ve learned that throughout his career Vonnegut has written as if speaking directly to his older sister Alice. Even after her death in 1958, when brother Kurt, Jr. was 36 and considered by many, including himself, to be a failed novelist, he continued writing to Alice. (See his 1976 novel Slapstick.)

Fates Worse Than Death delivers on its heavy consumer price tag. For starters, there’s Vonnegut’s even-handed assessment of Hemingway in the age of feminism and ecology: “If Hemingway had been a painter, I would say of him that while I often don’t like the subjects he celebrates, I sure as heck respect his brushwork.”

Here’s a typically Vonnegutian stop-&-stare moment, one of many jabs the Old Master gets off at his lifelong nemesis. “Well – the example of Christianity is not encouraging, actually, since it was nothing but a poor people’s religion, a servant’s religion, and would remain such if it hadn’t stopped taking the Sermon on the Mount seriously and joined forces with the vain and rich and violent. I can’t imagine that you would want to do that, to give up everything you believe in order to play a bigger part in world history.”

Kurt Vonnegut is one of the great purveyors of black humor in world history.

From my coat-pocket dictionary: Black Humor – A non-serious way of dealing with disastrous events and serious subjects. Black Humor is often used to discuss a painful or gruesome incident lightly.

The interviewer wants to know if the Old Black Humor Master laughs at his own writing while he is writing it?

“I know a joke when I see one,” says Kurt Vonnegut. “It’s a lot like making a movie, which is partly opportunism. If something wonderful appears suddenly while you’re shooting and it’s not in the script, hell, you feel like a genius when you leave it in. And I’ll be writing away and I’ll suddenly realize I’ve laid a foundation for a pretty elegant joke without meaning to, and so all I have to do is sort of pull the string on the joke with a couple of more sentences and suddenly it’s very funny. When I teach writing I say that you should tell the reader as much as you possibly can as quickly as you can so that in case you drop dead the reader will be able to finish the book.”

The interviewer reminds the Old Master he has said he does not like to read his own books.

“Well, I’m embarrassed,” he replies. “An awful lot of what we do is a result of things that happen to us in childhood. I don’t think I’m the first to point that out. And the feeling in my family was that we didn’t want any publicity. Whatever problems we had, we kept quiet about it, didn’t talk about it, including my mother’s insanity. So I always have the feeling that I blabbed. I blabbed, I told it all. I was the youngest kid in the family, and the youngest kid in the family is loaded with secrets from his older siblings. You know, ‘If you tell Mother I’ll kill you.’ Then here I am going blab blab blab blab blab book after book after book, so I think I feel guilty about it.”

“Well, I’m embarrassed,” he replies. “An awful lot of what we do is a result of things that happen to us in childhood. I don’t think I’m the first to point that out. And the feeling in my family was that we didn’t want any publicity. Whatever problems we had, we kept quiet about it, didn’t talk about it, including my mother’s insanity. So I always have the feeling that I blabbed. I blabbed, I told it all. I was the youngest kid in the family, and the youngest kid in the family is loaded with secrets from his older siblings. You know, ‘If you tell Mother I’ll kill you.’ Then here I am going blab blab blab blab blab book after book after book, so I think I feel guilty about it.”

Vonnegut’s boyhood idol was John Dillinger. Dillinger was an Indiana man. Kurt, Jr. was an Indiana boy. In those days of desperation, the nation’s economy had stopped. In Indiana, farmers lost money and banks foreclosed on farms. Farmers believed banks had taken their money. John Dillinger robbed banks, and never killed anybody. “But as somebody else pointed out,” says the Old Master, “the people who were with him killed plenty of people.” He breaks into dark, sardonic laughter which trails on and on with no loss of malicious hilarity until finally slowing as his poorly drawn breath begins to give out, and bogging down entirely amid the gelatinous goop in his throat. “But Dillinger was Robin Hood,” he adds, “and Americans are a rebellious people, or were back then.”

Vonnegut’s kind of rebellion has always contained heaping spoonfuls of wit and doom saying. In recent years, he has added a pinch of horse sense sermonizing. With Planet Earth creeping up on self-annihilation, Vonnegut has compiled in Fates Worse Than Death a list of the “stern but reasonable” surrender terms Nature has offered to us humans. It is a simple list, suitable for the refrigerator door. Clip it out. Post it.

1. Reduce and stabilize your population.

2. Stop poisoning the air, the water, and the topsoil.

3. Stop preparing for war and start dealing with your real problems.

4. Teach your kids, and yourselves, too, while you’re at it, how to inhabit a small planet without helping to kill it.

5. Stop thinking science can fix anything if you give it a trillion dollars.

6. Stop thinking your grandchildren will be OK no matter how wasteful or destructive you may be, since they can go to a nice new planet on a spaceship. That is really mean and stupid.

7. And so on. Or else.

Remember the vintage-Vonnegut final image of Cat’s Cradle? The world is being destroyed with terrible inevitability by ice-nine. Bokonon, a calypso prophet, has written the final sentence for the holy Books of Bokonon: “If I were a younger man, I would write a history of human stupidity; and I would climb to the top of Mount McCabe . . . and I would make a statue of myself lying on my back, grinning horribly, and thumbing my nose at You Know Who.”

Thirty years later, now within sight of seventy, Kurt Vonnegut wiggles his fingers like a plume at the Almighty. He has Bronx-cheered the Requiem Mass with a re-write of Pope St. Pius V’s official 1570 Council of Trent version. In Vonnegut’s new promulgation of the Mass, God is removed entirely from the whole fire-and-brimstone affair and instead Vonnegut places blame where blame belongs: “We shall dissolve the world into glowing ashes, as attested by our weapons for wars in the names of gods unknowable.”

So it goes.

In the new book there is a brief episode on a tour bus. The world famous American writer Kurt Vonnegut asks the world famous German writer Heinrich Boll what is the most dangerous flaw in the German character. Boll replies, “Obedience.”

The interviewer cannot resist putting the same question to Kurt Vonnegut. What is the most dangerous flaw in the American character?

“I don’t think we’re a flawed people. I think we have a flawed society. What’s crippling about Americans now is that they’re unable to organize in order to make their feelings felt as opposed to those in corporations and the government. But we’re a polyglot society. We could never fall apart like the Russians did because we’re all mixed up. They had their people segregated in their own soviet.”

The new book contains more than only Vonnegut’s writing, notably a 60th birthday tribute delivered to him by Bernard V. O’Hare, a friend since WWII. The two American soldiers were captured by German soldiers and taken to Dresden, where they were imprisoned in an abandoned slaughterhouse. Soon after, Allied planes firebombed the city, reducing most of it to ashes, but O’Hare & Vonnegut survived by taking shelter in a meat locker. O’Hare’s speech includes this passage: “Our captors told us that ‘for you the war is over’ and sent us to Dresden. We lived in a slaughterhouse. In the firebombing of that city by persons we thought were friends it proved to be the best house in town.”

U.S. Army PFC Vonnegut’s account of imprisonment gets more detailed.

U.S. Army PFC Vonnegut’s account of imprisonment gets more detailed.

“I bunked with [Crone] when he died. One morning he woke up and his head was swollen like a watermelon and I talked him into going on sick call. By midday word came back that he had died. You remember we slept two in a bunk so I had to shake Crone several times a night and say, ‘Let’s turn over.’ I recall how in the early morning hours the slop cans at the end of the barracks overflowed. Everyone had the shits, and it flowed down the barracks under everyone’s bunk. The Germans never would give us more cans. Joe Crone is buried somewhere in Dresden wearing a white paper suit. He let himself starve to death before the firestorm. In Slaughterhouse-Five, I have him return home to become a fabulously well-to-do optometrist.”

The interviewer and the Old Master are getting on well, nodding in ironic agreement over the abysmal yet hilarious state of things. The interviewer, seeing as he views Vonnegut as an intellectual granduncle of sorts, ventures to ask a question which involves his own father, a truck driver, thick with gristle and reticence, a USMC PFC in WWII, who once said to his son he did not believe there is a hell. “This is hell.”

How does the Old Master respond to such a statement?

“Well, it’s actually been done in literature,” says Kurt Vonnegut. “Finally the guy announces that this is hell. And somebody else says, ‘Well where on Earth did you think you were?’”

The Old Master falls into another grim attack of hacking laughter. He convulses with wheezing, his guffaws rising from some immense pit of human ugliness. When he recovers, Kurt Vonnegut continues. “I am surprised that suicide isn’t more common than it is. I’m writing about Christopher Columbus now, because I’ve been asked to, and I see that the Indians, when they weren’t killed by the Spaniards, died of disease. I’m surprised they didn’t commit suicide, the white man treated them so badly. In 1493, one year after they got here, the Spaniards were hanging thirteen Indians at a time in honor of Christ and the twelve Apostles.” More rattling, malignant laughter, swirled in phlegm.

It is widely known, Kurt Vonnegut himself tried to commit suicide several years ago. “It was a very serious attempt. I don’t take pills myself, but my wife had a lot of them, so I took a lot of them. It was all right. It would have been all right if I had just fallen asleep and died, but apparently I was sleeping very noisily and someone came up to see what the hell the trouble was.”

There are other questions which must be asked of the Old Master before we end. Does he vote?

“Yes.”

What does he remember about Carnegie Tech, where the Army sent him after basic training to keep him occupied until it was time to ship him off to The Battle of the Bulge?

“I remember flunking thermodynamics. In technical courses, this is the filter that separates the men from the boys. All of a sudden, it gets very tough and mystifying. That’s when a lot of people give up being scientists and engineers. And thermodynamics, oh shit. I had no chance to get a handle on it. As for Pittsburgh, I liked it except it was filthy because they hadn’t done anything about the soot and didn’t think they had too. Then after the war they found out they couldn’t get good people to come work for them because the city was so dirty. So they cleaned it up.”

A final question might give us still greater access to the puzzle box within the Old Master’s writing. Does he have a favorite composer?

A final question might give us still greater access to the puzzle box within the Old Master’s writing. Does he have a favorite composer?

“Yes, but not for the noblest of reasons,” says Kurt Vonnegut. “I very much like Erik Satie.” Then, sounding rather (it must be said) Twainesque, he adds parenthetically, “although in France I’m not well thought of and I don’t have a very good time when I go there.”

But Satie! What does he like?

“About Satie, I just have a feeling that I could do it.”

Erik Satie: Prelude #3 – (1:11 Minutes)

The interviewer knows something about Satie, and recalls the French Musical Dadaist’s motto for constant change in the arts: “To place one’s trust in the young is something that is always absolutely essential.”

“Yes,” says Kurt Vonnegut, ready to stop talking. “I think art should respond to its times, and sometimes it does so very upsettingly.”

Calling himself “an old poop,” the Old Master has again responded very upsettingly, with Fates Worse Than Death. “If we desolate this planet, Nature can get life going again. All it takes is a few million years or so, the wink of an eye to Nature. Only humankind is running out of time.”

His cynicism is still black as the charred remains of a child discovered among the ashes of a great Baroque city. (“I will say anything to be funny, often in the most horrible situations.”) Walking the road home, Kurt Vonnegut continues to pull the string on many a joke: “What other fates worse than death could I name? Life without petroleum.”