Memories of learning, maturing

with Richard Brautigan

by Dennis Bartel

PITTSBURGH POST-GAZETTE (November 5, 1984)

Just over a week ago came word that Richard Brautigan was dead. His decomposed body was discovered by friends in his home in Bolinas, Calif., north of San Francisco. Apparently, he had shot himself.

Brautigan had always been dismissed by the Academy. The Academy said his writing was not rigorous enough; it spoke to our immediate time, not time immemorial; it was for those readers too lazy to read the real stuff in Ginsberg and Ferlinghetti. Many people thought Brautigan had stopped writing years ago.

Of course, that’s not surprising. Brautigan went out of fashion with octagonal eyeglasses and orange sunshine, though a few of his books were reprinted by Seymour Lawrence of Delacorte Press.

Of course, that’s not surprising. Brautigan went out of fashion with octagonal eyeglasses and orange sunshine, though a few of his books were reprinted by Seymour Lawrence of Delacorte Press.

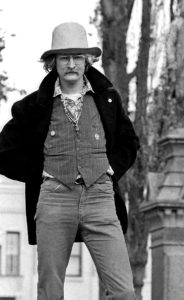

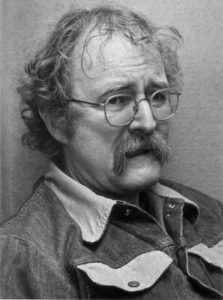

They say Brautigan was born in Spokane, Wash. He seemed instead to have sprung from some mushroom hallucination. Dirty blond hair like a Lhasa Apso’s, a broad white forehead that invited a playful knuckle-rap, a mustache draped over his mouth like a poncho, the eyes of a man who was neurotic and afraid, but still looking on with the curiosity of a 10-year-old.

In 1965 his first book, A Confederate General From Big Sur, sold 900 copies in Northern California, and was then buried. In 1968 it was excavated by hippies. Here was a man, they said, who seemed to understand his place in the firmament; who had befriended the world.

From Brautigan we first learned much about erotic wit, about earning one’s wisdom honestly, about satire with compassion. We could have learned these lessons elsewhere, but the fact is we learned them from Brautigan – and at the same time he was learning them.

He matured from a yammering, mischievous school boy to a serious, albeit irreverent, writer right before our eyes.

Those who wouldn’t accept his early role as a generation’s spokesman, as a writer who did not fear ridicule as he pushed to the limit of humility without crossing over into silence, those people missed Brautigan’s best work. For in 1975, at the awakening age of 40, Brautigan began writing with a subtlety and intricacy not seen in American literature since Mark Twain.

Here’s one of those later chapters, in its entirety, about the slow disintegration of a love affair, “The Sandwich.”

“Are you hungry?” Bob asked Constance.

She was sitting at the kitchen table, half-looking at a magazine.

“No,” she said. “I just had a sandwich.”

By the mid-’70s Brautigan had become a dated icon to the Woodstock generation. He was funnier than ever, more insecure than ever, but no one was reading him.

A lot of his descriptions were clichés. But they gave his prose an old-comfortable-clothes quality. Reading Brautigan was fun, non-threatening, but never empty. He called himself a heart-broken American humorist, and speaking of himself in third person he said:

He would have enjoyed life a little more if he had been able to laugh at it. When he was writing things that later on people would praise as some of the best humor of the century, he didn’t laugh when he wrote them. He didn’t even smile.

Those early Brautigan books now dissolve in our hands like burnt incense. Perhaps his later books – Sombrero Fallout, Willard and His Bowling Trophies, June 30th June 30th – will too. But while we had them they brought clarity and kindness to a lot of neurotic lives.

Brautigan’s best book, The Toyko-Montana Express, ends:

ATTENTION SUBSCRIBERS TO THE SUN: GOOD MORNING

Good morning, Richard.