The Górecki

by Dennis Bartel

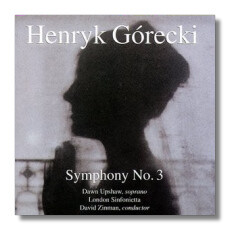

With the passing of Henryk Górecki, I revisited some items I wrote about the composer and his phenomenon of a symphony, the Third, “Symphony of Sorrowful Songs,” back when it first swept astonishingly upon the scene. There was such excitement over this deeply elegiac record. It went to No.6 on the British charts, the British pop charts. Music Week (the UK’s Billboard) declared the hysteria over The Górecki, as the symphony quickly became known, “unprecedented.” In England, the CD out-sold Michael Jackson. Once The Górecki jumped the pond the vanguard markets in the U.S. for these strange new sounds were L.A., D.C., and Boston. Elektra Nonesuch reported sales topped 150,000 in a heartbeat. The Górecki built a nest at the top of the classical charts for months, and then sales rocketed higher with the airing on TV of a Tony Palmer film on the work, featuring the same musicians who made the CD, soprano Dawn Upshaw, and the London Sinfonietta led by David Zinman. In Australia, The Górecki likewise jumped to the pop charts. Japan discovered it! Critical reaction gushed with superlatives. No less a confirming force than Time Magazine called The Górecki “one of the greatest and most mysterious works of our time.” All this hysteria for a mournful score of loss and disillusionment, by an unknown and reclusive sixty-year-old man living in small-town Poland. Why, and how?

With the passing of Henryk Górecki, I revisited some items I wrote about the composer and his phenomenon of a symphony, the Third, “Symphony of Sorrowful Songs,” back when it first swept astonishingly upon the scene. There was such excitement over this deeply elegiac record. It went to No.6 on the British charts, the British pop charts. Music Week (the UK’s Billboard) declared the hysteria over The Górecki, as the symphony quickly became known, “unprecedented.” In England, the CD out-sold Michael Jackson. Once The Górecki jumped the pond the vanguard markets in the U.S. for these strange new sounds were L.A., D.C., and Boston. Elektra Nonesuch reported sales topped 150,000 in a heartbeat. The Górecki built a nest at the top of the classical charts for months, and then sales rocketed higher with the airing on TV of a Tony Palmer film on the work, featuring the same musicians who made the CD, soprano Dawn Upshaw, and the London Sinfonietta led by David Zinman. In Australia, The Górecki likewise jumped to the pop charts. Japan discovered it! Critical reaction gushed with superlatives. No less a confirming force than Time Magazine called The Górecki “one of the greatest and most mysterious works of our time.” All this hysteria for a mournful score of loss and disillusionment, by an unknown and reclusive sixty-year-old man living in small-town Poland. Why, and how?

Written in 1976, “Symphony of Sorrowful Songs” had been known for years in some circles. There were three previous European recordings, one of which was used as the soundtrack for the French film Police, with Gerard Depardieu. But while the response to the symphony was often intense (Górecki remembered an early performance in London when during the silence at the end someone in the audience swore) it was no bellwether for the chart-topping ignited by the Upshaw/Zinman CD.

The Górecki was called crypto-minimalist for its deceptively simple use of repetition and poignant modal melodies, evocative of Renaissance sacred music, combined with a starkly modern sensibility. All three movements are long and slow: Lento, Lento e Largo, Lento. For the vocal texts, Górecki chose three disparate poetic images of a mother losing a child.

The Third Symphony unfolds gradually in layers of repetition, as the double basses play a canon and it is passed upward to the other strings and constructed into a vaulted ceiling of sound. The entrance of the piano signals the start of a setting of the Holy Cross Lament, “My chosen and beloved Son,” an amalgam of medieval chant, hymn, and folk song, in which Mary mourns the death of Christ. The canon returns at the end of the movement (though it seems to have been playing silently all this time), descending back to the double basses.

The next movement is a setting of the opening four lines to the Polish Ave Maria. Górecki explained that he found these words in a book about the Nazi occupation of Poland. They had been carved into the wall of cell No.3 in the basement of “Palace,” the Gestapo headquarters in Zakopane, Poland, beneath which was the signature Helena Wanda Blazusiakowna and the words “18 years old, imprisoned since 26 September 1944.” Zakopane is in the mountainous region of southern Poland known as Podhale, a fact that is also reflected in the musical language of this second movement. Górecki said, “I adore Podhale and wanted to create the feel of the mountaineers’ music.”

The finale is likewise rooted in Polish folk music. While composing his Third Symphony, Górecki searched countless collections of folk songs for a suitable melody to treat canonically. “But in the end,” he said. “I composed one myself in the style of folk songs and using part of a church song collected by a priest.” Górecki also made subtle references to the powerful heartbeat of Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony and the uniquely Polish rhythm of Chopin’s Mazurka Op.17 No.4. The text was derived from a Podhale folk song portraying a mother lamenting the loss of her son in battle. While the entire Third Symphony is colored in varied shades of gray, the final moments are alight with transcendence.

Does this sound like a hit record? I asked the maestro who made the record why he thought “Symphony of Sorrowful Songs” had captured a broad public’s attention. “I have absolutely no earthly idea,” said Zinman, “with the exception that I think this piece makes a tremendous impression on anyone who hears it. It speaks to them in a kind of mystical way. Maybe that’s what we need in these times.”

Does this sound like a hit record? I asked the maestro who made the record why he thought “Symphony of Sorrowful Songs” had captured a broad public’s attention. “I have absolutely no earthly idea,” said Zinman, “with the exception that I think this piece makes a tremendous impression on anyone who hears it. It speaks to them in a kind of mystical way. Maybe that’s what we need in these times.”

A few years before The Górecki, studies in music psychology, using new brain-measuring technology, conducted in Switzerland helped scientists discover that the left and right hemispheres of the brain react separately to musical sounds. Discordant (clashing) music stimulates only the left, or verbal, logical and arrhythmic hemisphere, while concordant (harmonious) music stimulates the intuitive, emotional, and rhythmic right hemisphere. Schoenberg and Boulez were identified as left-hemisphere composers; Beethoven, Debussy, certain music from the Far East, and most certainly The Górecki were on the right.

A specialist in the field, Dr. Paul Robertson, pointed out that “living as we do in an excessively verbal culture with its constant bombardment of external stimuli, left hemisphere-dominated music can leave us starved of emotional and spiritual nourishment.”

Whatever the reasons, Górecki was no less mystified at the success of his Third Symphony. “It’s a wonder, a miracle. It’s fantastic for an old man to have such understanding in foreign lands. I’m glad my music has helped people enlarge their musical boundaries.”

Górecki was a reticent man and a devout Catholic who was once officially censured by the Communist regime for composing a work to welcome the Pope on his visit home to Poland. He lived all his seventy-six years in the same coal-mining southwest district of Poland called Silesia, except for a brief period of study in Paris with Olivier Messiaen in the early 1960s. His home was in the industrial town of Katowice, but he composed most of his music in the nearby mountain village of Chocholow. In every piece of mine,” said Górecki, “there is something of the Tatra mountains. I need them like fish need water, like a man needs air. The folk music is still alive, right up to today. It’s not just in my ear, it’s in my blood. And it’s not just the music, but the crafts, the buildings, the paintings, the glass works, the clothing. Every day I’m not in Chocholow is a lost day.”

And yet, in that mountain village early in his career, Górecki first composed music that made him a shining star of the Polish avant-garde, massive, dense, passionate orchestral outpourings of serialism at its most searing, exploding with violent, conflicting sonorities. Communist authorities grew wary of him.

Then about age forty, Górecki immersed himself in Catholicism and rigorous study of church music and folk songs. His own music took on a simpler language, more melodic and more intimate, while paradoxically also becoming more mathematically complex. At the height of this aesthetic, Górecki composed “Symphony of Sorrowful Songs.”

“The most important problem for me at the end of the twentieth century,” Górecki told the members of the USC Thornton Symphony Orchestra as they rehearsed a performance of his masterpiece in 1997, “is the continual lack of time. We are always in an awful hurry and  still we waste an incredible amount of time, for instance in front of the TV or in a car. While I do like some aspects of our ‘fast’ civilization – I love to fly in airplanes, I am fascinated with cosmic adventures, trips to the moon or Mars – and we do live in astounding times, still, here, in this music, we have to surrender ourselves to this other dimension of time. We have to slow down. Only then the sonority will be fantastic, the higher the music will go, the more distinctly it will sound. I dream of writing such tranquil music. I do not want to compose anything that echoes the modern ‘rush.’ It has to be calm. Life is too beautiful to be wasted in this way, by rushing things so much.”

still we waste an incredible amount of time, for instance in front of the TV or in a car. While I do like some aspects of our ‘fast’ civilization – I love to fly in airplanes, I am fascinated with cosmic adventures, trips to the moon or Mars – and we do live in astounding times, still, here, in this music, we have to surrender ourselves to this other dimension of time. We have to slow down. Only then the sonority will be fantastic, the higher the music will go, the more distinctly it will sound. I dream of writing such tranquil music. I do not want to compose anything that echoes the modern ‘rush.’ It has to be calm. Life is too beautiful to be wasted in this way, by rushing things so much.”